Is Nonviolent Resistance Past Its Prime?

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Linda Villarosa

In “We Refuse,” Kellie Carter Jackson explores the many forms of activism that oppressed people have resorted to and offers a more nuanced picture of their lives.

In his 1958 memoir “Stride Toward Freedom,” the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. laid out a series of principles — courage, friendship, spiritual transformation and so on — for combating racism and other forms of oppression. Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi and Jesus Christ, King urged that the acceptance of suffering, even violence, without retaliation put one in accord with the universe and armed just people with the power to defeat hate.

The practitioners of nonviolence fought with “the weapon of love,” King wrote, and their method became a foundational tactic for many civil rights activists. Think of the 1950s and ’60s, when young men and women were shoved and spit on for sitting at lunch counters. Ideally, they simply waited out the assault without so much as raising a hand. Underlying this strategy is the hope, in King’s words, that “unearned suffering is redemptive” and can open the door to understanding.

Since the civil rights era, iterations of King’s nonviolent approach have remained the most familiar, acceptable and celebrated forms of opposition to racial oppression. You can see the roots of King’s philosophy of nonviolence in the marches and hashtags in the summer of 2020 after the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and many others.

But is this singular approach the best that activists can do, even when fine-tuned for different generations or movements? Where do they look for other models? In her compelling and often counterintuitive new book, “We Refuse,” Kellie Carter Jackson, a professor of Africana studies, argues that the usual chronicles of this resistance are both narrow and watered down. “Our culture’s fixation on nonviolence has caused us to miss entire histories of Black responses to white supremacy,” she writes. “Nonviolence on its own is not at all expansive enough to rectify the harm that has been caused by racism.”

Her book warns against the dangers of misremembering the past and offers a broader and more nuanced picture of resistance through the frame of refusal. It is “a halting hand, a pointed finger waving from side to side or a powerful raised fist. It is a barrier that prevents oppressed people from being consumed.”

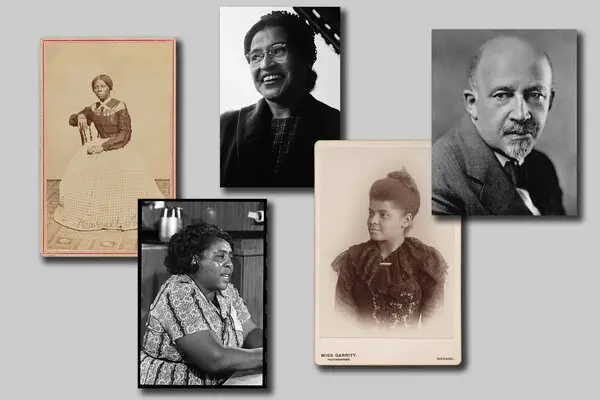

Our online exhibits include more information about the Civil Rights Era and activists.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.