Posts Tagged ‘Segregation’

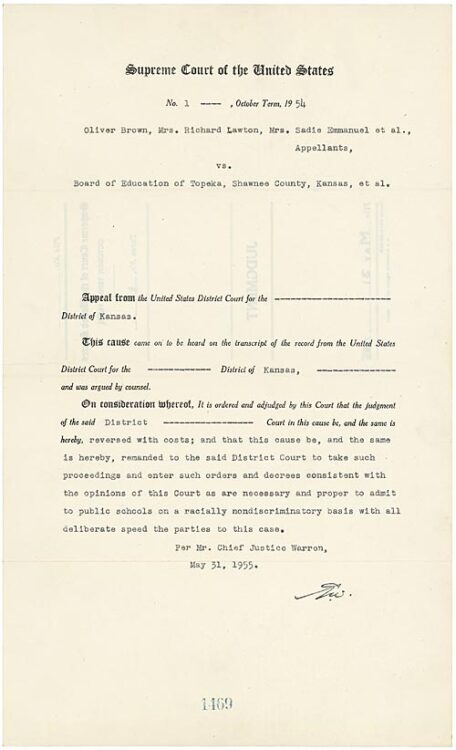

This Date in History: Brown v. Board of Education Is Decided

Heather Cox Richardson discusses two landmark civil rights anniversaries this weekend, includinf the one that barred school segregarion.

Read MoreThe Justice Department ended a decades-old school desegregation order. Others are expected to fall

The public disagrees whether revoking forced desegregation laws in Louisiana will lead to more education inequality for some students.

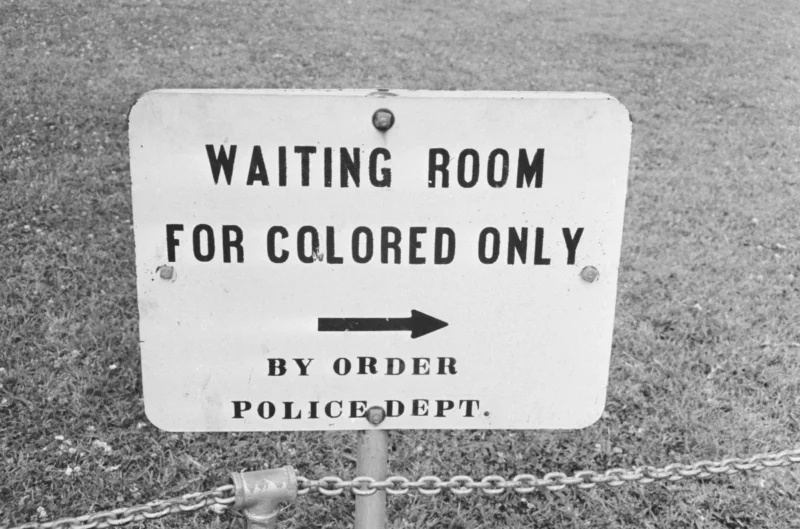

Read More‘Segregated facilities’ are no longer explicitly banned in federal contracts

Although the federal laws are mostly symbolic because individual states ban segregation, many argue that the change is still negative.

Read MoreWatch: Brown at 70—A Reality Check on School Segregation

Dr. Camika Royal, Sharif El Mekki, Dr. Kelly Hurst, and Dr. Gary Orfield joined Word In Black to talk about modern school segregation.

Read More7 Facts About Modern School Segregation

Segregation in schools is illegal on paper but functionally still happens across the nation–and it may be getting worse.

Read MoreBlack couple accused of smelling ‘like weed’ are kicked out of Memphis eatery, racial discrimination suit says

A Black couple from Memphis is suing a local restaurant for kicking them out, claiming they “smelled like weed” despite their own protests that they don’t smoke marijuana.

Read MoreMorgan State University 80-year-old segregation wall comes down in Baltimore

For over three fourths of a century, students at Morgan State University walking down Hillen Road would walk past a red brick wall. Unbeknownst to most, the wall was built by White residents in the 1930s in response to the increasing enrollment of Black students at Morgan State, a historically Black institution. The construction of the “Spite Wall” at Morgan State epitomizes the hate that does not welcome Black students. Destroying this wall is a collaborative effort to reconstruct and expand the University.

Read MoreBlack leaders on Buffalo’s East Side are building markets to address food insecurity

A proposed food co-op might ease the burden on some Buffalo residents who live in what’s known as a food desert.

Read MoreThe Marines were last to integrate. Here are the stories of the first Black recruits.

Some of the first Black recruits to the U.S. Marine Corps are telling their stories and receiving honors for their sacrifice.

Read More102-year-old WWII Veteran from Segregated Mail Unit Honored

102-year-old Romay Davis was honored for her service in the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, which delivered mail during WWII.

Read More