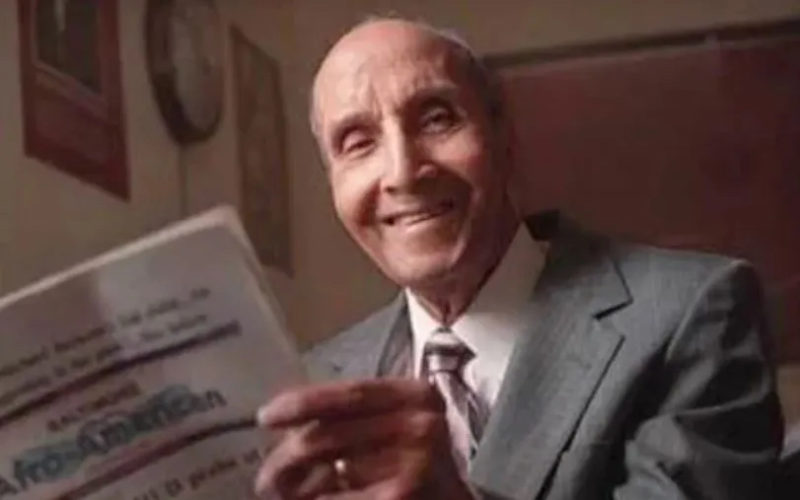

Before today’s black sports journalists there was the great Sam Lacy

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

by Stephen Borelli, USA Today

Sam Lacy looked out at the field on April 15, 1947. It was a day in New York City predicted to be partly cloudy, perhaps in more ways than one. Every time the ball was hit in Jackie Robinson’s direction, the sportswriter felt a lump in his throat. He feared the stress would be too much for Robinson to handle.

Lacy listened to the crowd.

Come on, Jackie

We’re with you…

There was reason to exhale.

“Branch Rickey made good riddance of bad rubbish here, Tuesday, when he erased the color line in big league baseball and played Jackie Robinson at first base,” Lacy began his front-page article in the Afro-American newspapers.

It was a moment for which Lacy had waited his entire career, if not his life. But the fight was not over.

Lacy had turned 42, fittingly, on the day in 1945 when Rickey signed Robinson. He would spend three-plus years on the Robinson beat, enduring “hell” at times, as Lacy’s son put it. He would spend eight decades as a journalist, typing out his stories from spots around the country and the world, then, in his later years, writing them out in longhand. When he was in his 90s, he would awaken in the early morning – the middle of the night, really – and drive the 40 or so miles from his Washington, D.C., apartment to the offices of the Afro in Baltimore. If you asked Lacy, whose wife had died in 1969 and whose two children were pursuing their own careers, what else was he going to do?

More to the point: What else had he not done? To look at Lacy’s 99 years is to live the history of social justice in sports as it was made, and as it continues to be made. It is history that Lacy has quietly yet profoundly influenced.

“Every African American athlete owes Sam Lacy a debt of gratitude,” Pro Football Hall of Famer Lenny Moore would say when Lacy died in 2003.

Lacy pushed for integration and, ultimately, for equality in sports well before Robinson and well after him. His efforts effected change and eventually landed him in the writers’ wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He didn’t make it there until 1997, when he was nearly 94. His character was left out of the movie “42,” which was released in 2013, despite Lacy’s deep connection to and influence over Robinson’s story. He has somewhat faded into the background since he died almost 20 years ago.

A look back at his life and career shows how much of a forerunner he was to the advocates within the Black sports community today who continue the push for change.

“I think about Sam a lot because he really was a guiding light in terms of what my role is in the struggle,” says sports columnist William Rhoden, whom Lacy mentored as a young reporter in the mid-1970s at the Afro. “And it’s the same thing I would pass down now to young, Black sportswriters to appreciate all of these great opportunities…”

“If he were alive today and he saw what Mike Wilbon was accomplishing,” Rhoden says, “what Stephen A. Smith was accomplishing, and other guys, I think he’d be happy about it. But knowing him, he’d also offer critiques.”

Enjoy the complete article here.

For more Breaking News click here.

For more ABHM galleries click here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.