Reckoning with Family Secrets in Best Seller, In the Pines

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Summary of Los Angeles Times’ article and conversation, “She was told her grandfather had saved a Black man. Then she dug up the ugly truth.”

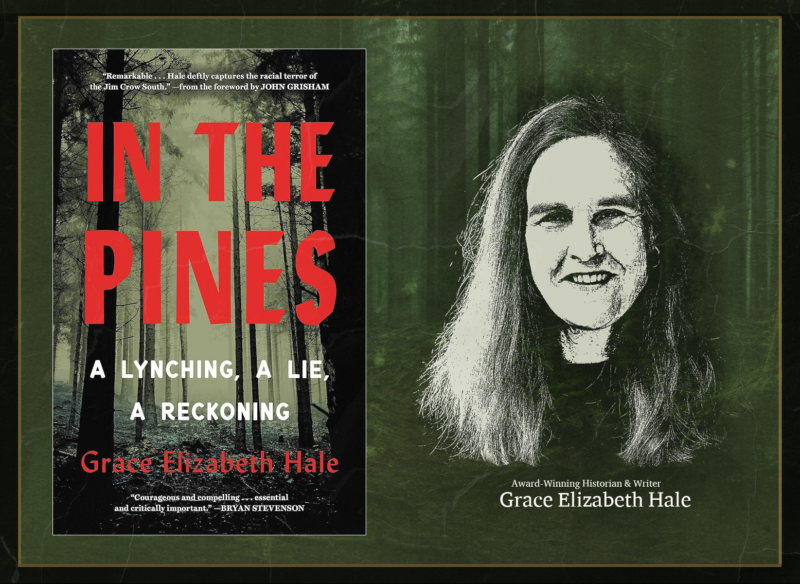

Grace Elizabeth Hale, an award-winning historian from the University of Virginia, has written a book about the 1947 lynching in Jefferson Davis County, Mississippi. Hale’s book, “In the Pines: A Lynching, A Lie, A Reckoning,” is more than just historical research. She discovered her grandfather, Oury Berry’s lie. His story that he had given an Atticus Finch-esque speech to the townsfolk to stop them from storming the jail and dragging Versie Johnson off to a gruesome death wasn’t true.

The story her family tells is that Johnson, a Black man, was accused by local men of raping a pregnant White woman. Supposedly the woman never came forward because she was suspected to have possibly been Johnson’s consensual lover. The prisoner, Versie Johnson died shortly after arrest, purportedly during an escape attempt. This was made up Hale learned and just the cover story.

In fact, Johnson was murdered by law enforcement under direction of the man Hale had known as Pa.

Hale started digging beneath the family lore back in graduate school, realizing this family story couldn’t be true the way it was described to her. She came to realize after events in Charlottesville, VA that she couldn’t help the United States reexamine its history without reckoning with her own. Hale’s journey led her to revisit this uncomfortable story. She had grown up with a story of her grandfather’s heroism. Hale realizes not wanting to know is symptomatic of a lot of white Americans. She wanted to make the point that this erasure of history is foundational to why racism and white supremacy persists.

Hale’s research revealed that the sheriff before her grandfather stopped a lynching multiple times, which was heartbreaking because it showed that it could be done. Her Pa had not stepped up and met the moment with courage and a sense of humanity.

Hale argued that there’s a porous boundary between law enforcement and vigilante behavior, and that different levels of government are at cross-purposes with each other, often turning the other way or encouraging vigilante violence.

Hale’s mother and other family members reacted negatively to her digging up the past. This story is not something her family accepts.

Read the complete article and conversation here.

For more stories like In The Pines: Shaking the Family Tree, Inheriting Home, The Family Tree, Our Town

For more Breaking News click here.

For more ABHvM galleries click here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.