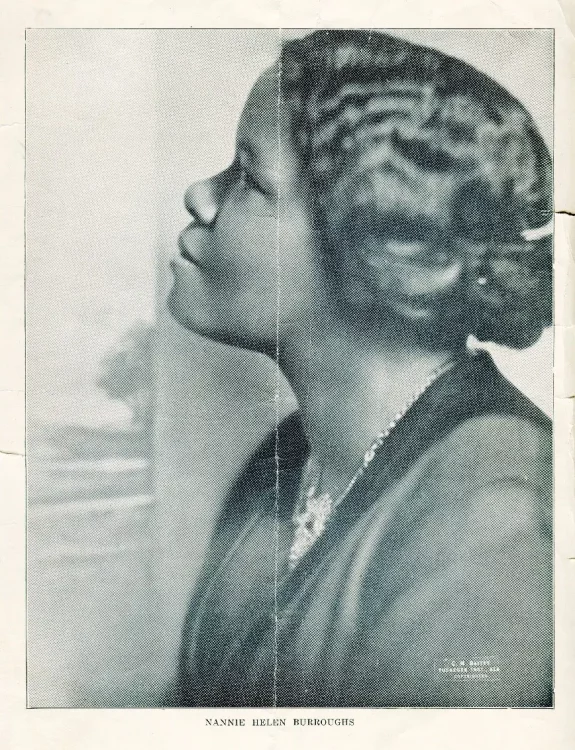

Nannie Helen Burroughs, trailblazing Black teacher and labor organizer

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Danielle Phillips-Cunningham, Washington Post

For Labor Day, we look at how she forged career paths and jobs for Black girls during the Jim Crow era

This Labor Day comes during a year of a historic upturn in labor organizing — including, just this month, a teacher strike in Columbus, Ohio. My research has delved into some of the long history of teachers’ community investment and institution-building that can strengthen our democracy.

In a forthcoming labor history, I explore the life of Nannie Helen Burroughs, founder of the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, D.C., in 1909. Burroughs was one of several trailblazing Black women educators and labor leaders. When Burroughs founded the NTS in 1909, Black women and girls were among the most exploited workers in the country. The Jim Crow South relegated Black youths to often-underfunded schools. Black women and girls were barred from jobs other than sharecropping and domestic service, the lowest-paying occupations in the U.S. economy. No laws protected them from rampant racial and gender violence.

Teaching was the only profession available to educated women like Burroughs. As with her pioneering friends Mary McLeod Bethune and Lucy Craft Laney, for Burroughs, teaching was never solely about lesson plans. Burroughs used her position as corresponding secretary of the Woman’s Convention (WC), the women’s auxiliary group to the National Baptist Convention (NBC), to democratize education by building her own school.

While teaching and presiding over the NTS, Burroughs worked at holding the country accountable to the citizenship promises of the Fourteenth Amendment. Through her curriculum and community organizing, she operationalized her philosophy that every young person deserved a quality education that opened access to any profession, living wages, safe and comfortable housing, clean water and nutritious food, and personal enjoyments. She often sacrificed her livelihood, personal comforts, and sometimes her physical health to meet the needs of her students and communities.

Learn more about Burroughs’ work.

Unsurprisingly, America has a racist history with labor that didn’t stop with slavery.

Check out more timely Black news.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.