Dead more than a century, now on research shelves, will Milwaukee’s early poor rest in peace?

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Claire Reid, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Over the next year, 831 early Milwaukeeans may finally be laid to rest in Forest Home Cemetery after more than a decade on university shelves.

Or they may linger awhile longer because of issues no one could have anticipated when they were originally buried in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The remains were originally buried in one of four Milwaukee County Grounds Cemeteries. The cemeteries were meant to be the final resting place for Milwaukeeans who died while in poverty, had physical or mental health disabilities, or were unidentified or unclaimed at the time of death.

In 2013, the 831 were exhumed to make room for the expansion of the Milwaukee Medical Grounds Complex in Wauwatosa, which houses Froedtert Hospital, Medical College of Wisconsin, Children’s Wisconsin and other health care facilities. Since then, the remains have been at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where they’ve been used for anthropological research.

[…]

What were the Milwaukee County Grounds Cemeteries?

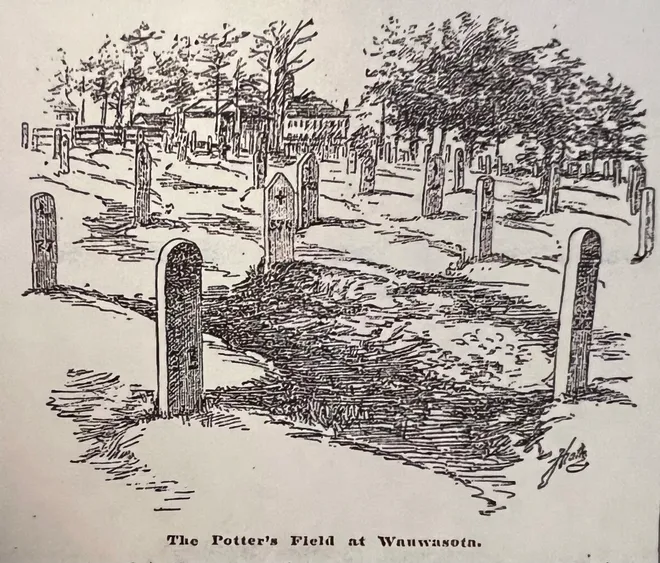

The Milwaukee County Grounds Cemeteries, also known as the Milwaukee County Poor Farm or the Potter’s Field of Milwaukee County, were four sections of a county-run cemetery for the poor, disabled, unclaimed and unidentified buried between 1852 and 1974.

It’s estimated that around 10,000 Milwaukee County residents were buried across all four cemeteries. An estimated 7,000 were buried in Cemetery 2, where the 831 came from.

Identification of anyone in Cemetery 2 is complicated because not all burials were recorded, some remains are under Doyne Avenue and an estimated 55% were disturbed in 1928 by the construction of the Milwaukee County Nurses’ Residence. Some of those were moved to Cemetery 3.

Then there were the disturbances from Medical Complex construction in the early 1990s and again in 2013.

Those buried in Cemetery 2 included mostly German immigrants at first, Houston said, “but then, over time, Irish, Poles, Italians, Greeks, Eastern European Jews, and eastern and southern European nationalities were also interred, reflecting the city’s growing diversity.” Native Americans and U.S.-born residents, especially Black Milwaukeeans, were buried there in the early 20th century.

Keep reading for more information.

Learn about Milwaukee’s relationship to race.

More Black news from Milwaukee and beyond.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.