A New Book Makes the Case that HBCUs Are Owed Reparations

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Curtis Bunn, NBC BLK

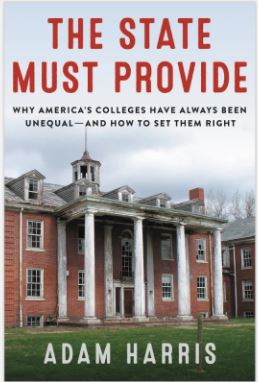

Adam Harris’ new book, “The State Must Provide,” examines the impact of racism on higher education and why Black colleges deserve financial restitution.

Why were the facilities superior at the predominately white school founded in 1950 than the historically Black university founded 75 years earlier, in 1875?

That fundamental question Harris pondered for a decade became the impetus for his newly released book, “The State Must Provide: Why America’s Colleges Have Always Been Unequal—and How to Set Them Right.” A reporter for The Atlantic, Harris crafted a comprehensive work that examines the vast history of how racial discrimination against historically Black colleges and universities manifested itself in governmental underfunding and undermining that augmented many of the schools’ lifelong struggles. The years of federal neglect led Harris to conclude that HBCUs are owed reparations from the overall bias they have suffered.

Photo credit: Harper Collins Publishers

He highlights laws like the Morrill Act of 1862, which was supposed to provide grants of land to states to finance the establishment of colleges specializing in “agriculture and the mechanical arts.” But state lawmakers misused or did not apply it to Black colleges.

That story was one of systemic inequality — and how that inequality should be repaired. The institutions that have profited from slavery, Harris said, “are the same institutions that were barring Black students from attending, while HBCUs were literally being shafted out of funding.”

“So while those institutions that were literally barring Black students, Black colleges were fighting for resources that were being stolen from them,” he added. “That’s why I talk about reparations. They are owed something. Thousands and thousands of Black students’ educational pathway was hampered by the way that the system has been set up.”

Harris said the amount of reparations could vary from state to state, but he pointed out a few examples of blatant unequal treatment that has plagued Black colleges.

A Tennessee government budget analysis determined that historically Black Tennessee State University is owed between $150 million and $544 million because of the state’s failure to honor the Morrill land grant agreement for 50 years. Instead of issuing TSU the same amount of government funding it issued the University of Tennessee, a predominantly white institution, as the law required, the analysis found that TSU did not receive any money from 1957 to 2006. Meanwhile, UT received its yearly allocation, and, in some cases, more than required.

Harris’ book also covers many other cases that illuminate Harris’ points on reparations. Although segregation has long ended, legally, Harris said systemic and institutional racism in higher education remains strong.

“If you look at a place like Auburn University,” he said. “It was 1985 when Bo Jackson won the Heisman as the best college football player in the country. That same day, a federal judge declared Auburn University the most segregated institution in the state of Alabama. They had about 2 or 3 percent Black students at the time.”

“Fast-forward to 2002,” he continued. “They had about 5 percent Black students. And look at Auburn now and it has fewer Black students, in total, than in 2002, even though its overall enrollment has grown by thousands. And so, the situation has not gotten a lot better. And a lot of cases in higher education, it has grown more stratified where the institutions that have the most resources and the most funding have the fewest Black students.”

“So there is this tendency to lean on this myth-making of America and sort of hero worship of American history and American life that is unproductive,” he said. “People should want to know history and the truth about how we got to this place and where we can and should go from here.”

More about Author Adam Harris HERE and to read the original article on NBC BLK HERE

Learn more about HBCUs and Black higher education HERE and HERE

More Breaking News here

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.