A crown branded onto bodies links British monarchy to slave trade

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Karla Adam, The Washington Post

Subheading

LONDON — Thumbing through the tanned pages of centuries-old records in the basement of the British Library, Nicholas Radburn came across an illustration that took him aback.

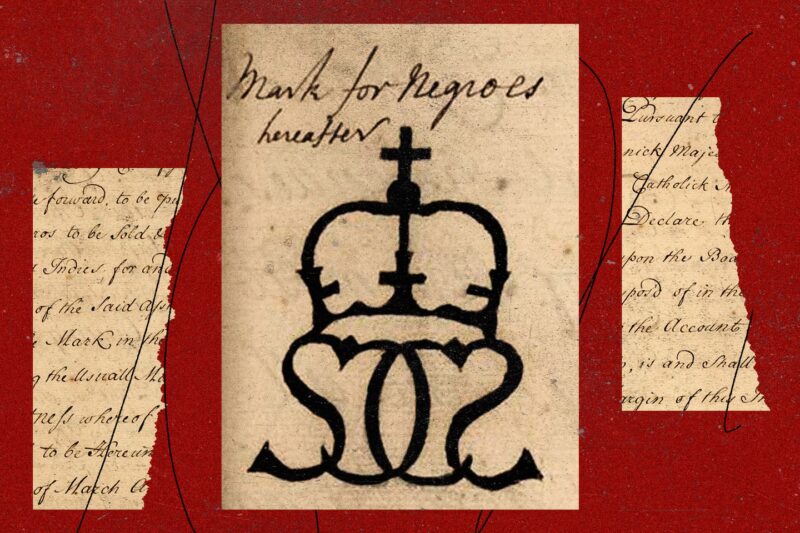

A crown resembling the iconic St. Edward’s headpiece from British coronations sat atop the letters S and C, apparently a stylized reference to the slave-trading South Sea Company. The accompanying text, written in 1715, declared that this was “the Mark henceforward, to be put upon the Bodys of the Negros to be sold & Dipos’d of in the Spanish West Indies,” under a contract between Britain’s late Queen Anne and Spain’s King Philip V.

“It was striking,” said Radburn, a historian at Lancaster University, who discovered the illustration as part of a project to digitize the records of the South Sea Company and its monopoly over the trade of enslaved Africans to the Spanish-held Americas.

Hot-ironing initials into the flesh of captives was a horrid but common practice in the era of the transatlantic slave trade. These brands were used to establish ownership claims, as a means of identification, for accounting purposes and to regulate sales.

Yet here was a highly unusual rendering of a brand that featured royal insignia, establishing a vivid link between the British monarchy and the slave trade.

Click here to read the response from the Royal Family.

Slavery happened in many places across the world. Click here to learn about the Triangular Slave Trade.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.