How many Black farmers are there in the US? Why we doubt the government stats

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Nathan A Rosenberg and Bryce Wilson Stucki, The Guardian

Numbers surged after changes to the agricultural census. Advocates say that’s not what they’ve seen on the ground

Earlier this summer, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) released data that suggested that, after years of decline, the number of Black farmers has grown to more than 45,000.

This is in stark contrast to the dire situation of Black producers in the 1990s, when a New York Times article predicted their coming extinction; Black farm numbers had fallen below 20,000 in that decade.

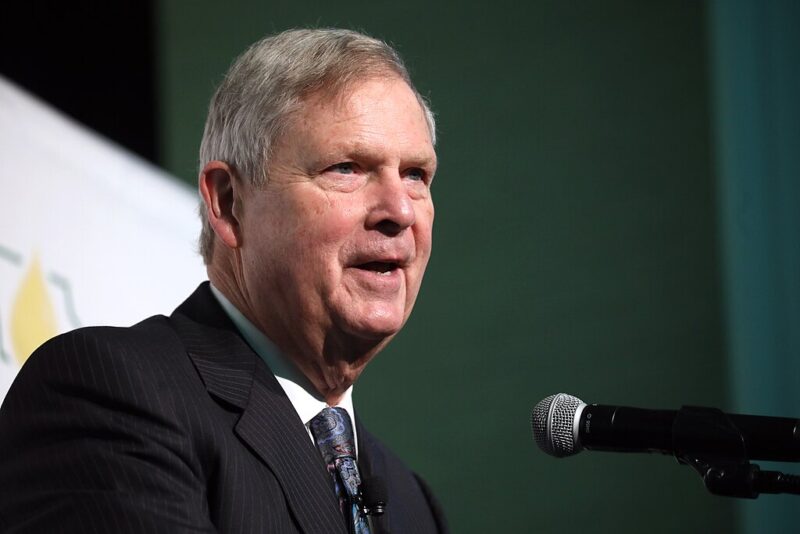

Yet we now seem to see a renaissance, something the agriculture secretary, Tom Vilsack, took credit for at the end of his first term as secretary of agriculture. In a 2016 essay, Vilsack wrote that the department was “forming new partnerships in diverse communities and regaining trust where it was once lost. This is most evident in the rising number of Hispanic and African American farmers.”

It’s a narrative that undeniably flatters the USDA, which stands to gain from public perception that there are far more Black farmers than there really are. After all, the department is the main culprit behind the huge land loss suffered by Black farmers in the 20th century, when African Americans lost almost 90% of their acreage, worth more than $326bn today.

And the department’s atrocious record of discrimination is by no means in the past. An award-winning 2021 Mother Jones investigation found that USDA agents still generated hundreds of discrimination complaints each year. The agency’s civil rights office, meanwhile, functioned as a “closing machine”, finding ways to dismiss or resolve complaints without real investigation or a favorable disposition for the complainnt. As one employee told us: “Doing right is a lonely, lonely, lonely business” in the civil rights office.

Discover how the latest agricultural census is misleading.

Just like the USDA prevented Black farmers from thriving, many Black families lost the land they briefly gained during Reconstruction.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.