How a white mob lynched a Black man, destroyed a city – and got away with it

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Bayeté Ross Smith, The Guardian

In 1919, white rioters stormed into an Omaha courthouse and dragged a Black jailed man who said he was innocent out to his death

Human skin melts at 162F (72C). Fifty degrees more and the blood boils.

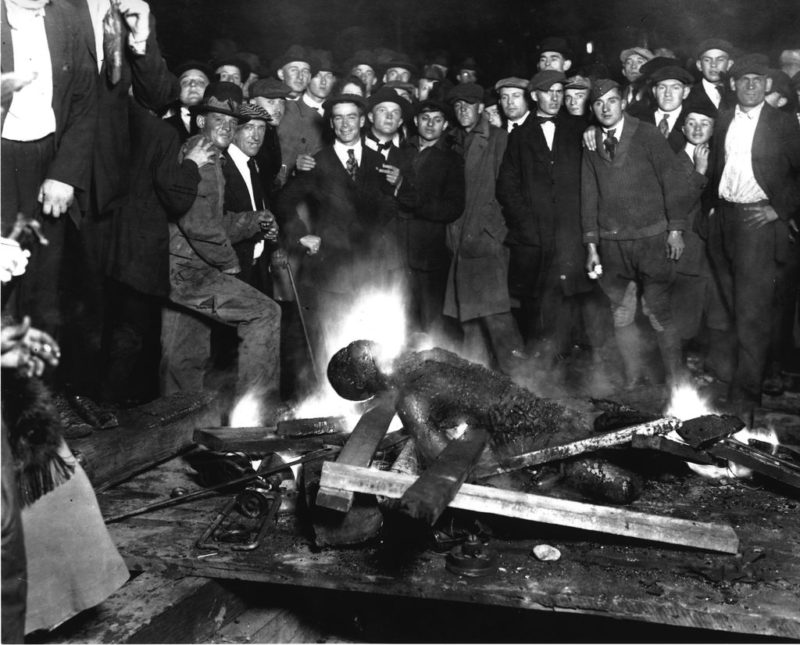

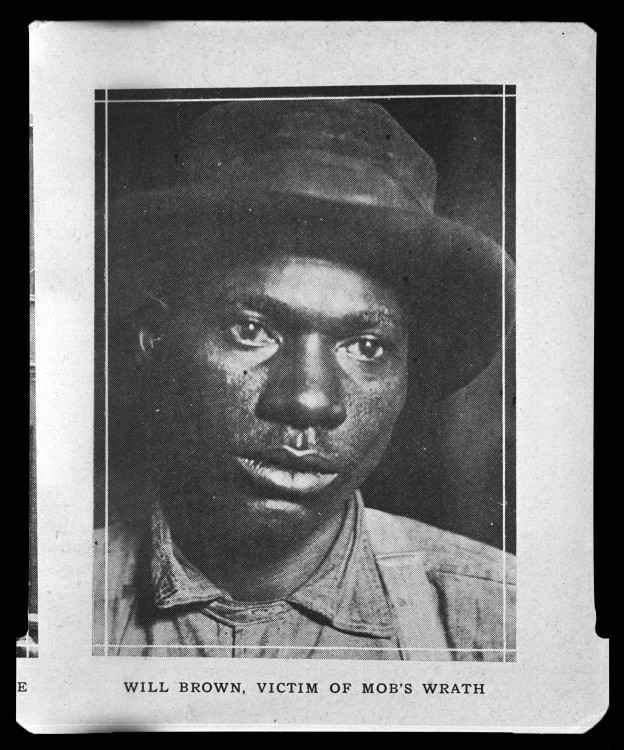

Within a matter of minutes after the crowd that lynched him put Will Brown into the raging bonfire at the intersection of 17th and Dodge streets in downtown Omaha, Nebraska, his bullet-riddled, mutilated body was destroyed. It was 28 September 1919, and the 41-year-old laborer had been pulled out of the Douglas county courthouse building four blocks away after a mob estimated to be between 5,000 and 20,000 white locals laid siege to it. Over two days one of the final, most dramatic occurrences of the fateful 1919 Red Summer unfolded in Omaha because a 19-year-old white woman cried rape at the hands of a Black man.

Returning home at midnight from a movie on 25 September, Millard Hoffman and Agnes Loebeck claimed a Black gunman robbed them, then dragged the young woman into a ravine and raped her. The Omaha Beeran a headline the next day: “Black Beast First Stick-up Couple”. Within hours of the alleged attack, the brother of the 19-year-old Loebeck combed the south Omaha community with several hundred, armed white men looking for the assailant. Someone in the group pointed out that a “suspicious negro” lived with a white woman in the neighborhood, and the mob went to a house at 2418 South Fifth St, finding Will Brown hiding under a bed in the home of Virginia Jones, a white woman whose lover, a Black man, Brown knew. The men dragged Brown to Loebeck and Hoffman, who identified him as the assailant, even though the frightened man suffered from debilitating rheumatoid arthritis. Omaha police took custody of Brown and transferred him to the courthouse jail.

I am innocent, I never did it, my God I am innocent. Will Brown

Over two days the percolating bloodlust from the white Omaha community grew, fueled by incendiary newspaper headlines, rumor and statements made by public officials such as those of the Mississippi senator John Sharp Williams, responding to the case, that “the protection of a woman transcends all law of every description, human or divine”. On the evening of 28 September, a white crowd attacked the jail where Brown was being detained with other prisoners – Black, white, male and female. Through the night, fires were set inside the building to force the police, court staff and jailors to release Brown. The newly elected progressive mayor, Edward P Smith, tried to reason with the crowd and refused to let them take Brown. He was seized and put in a noose to be hanged. Smith was cut down in time to be saved and taken to Ford hospital for treatment.

Inside the burning courthouse building, pleading with the sheriff not to be released to certain death, Brown reportedly stated over and over again, “I am innocent, I never did it, my God I am innocent.” It’s unclear based on historical records if he was pushed out by other prisoners, released by guards or pulled out by the attackers, but eventually Brown was stripped naked, beaten, hanged and shot before being placed on a bonfire. Then a frightened 14-year-old boy, later a 20th-century American acting icon, Henry Fonda, watched the hanging from a nearby building with his father. Remarking on the incident in a 1975 BBC interview, he said: “It was the most horrendous sight I’d ever seen. My hands were wet, there were tears in my eyes. All I could think of was that young black man dangling at the end of a rope.”

The corpse was dragged behind a car throughout the city the next morning. Nearly 2,000 members of the 26th Infantry restored order and maintained martial law to end the chaos, as well as protect the Black community in north Omaha. Without a service, graveside mourners, or even a headstone, Brown was buried in the local Potter’s Field cemetery with a marking which simply said “lynched”. It wasn’t until 2012 that a California donor gave him a proper headstone and grave marking. Last month, the city of Omaha unveiled a commemorative plaque outside the Douglas county courthouse to acknowledge what happened to Brown, Edward P Smith and the legacy of racial violence in Omaha from 28-29 September 1919. No one was ever tried for Brown’s death nor the attempted lynching of Mayor Smith.

Red Summers is a 360 video project by the artist and film-maker Bayeté Ross Smith on the untold American history of racial terrorism from 1917 to 1921. The project is funded by Black Public Media, Eyebeam, Sundance Institute, Crux XR and the Open Society Foundations.

Read a full documented and detailed account of the riot and spectacle lynching by the Nebraska Historical Society here.

Learn about another iconic spectacle lynching in the North here.

More Breaking News here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.