Descendants of enslaved man, plantation owner unearth past at Maryland cabin

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Dana Hedgpeth

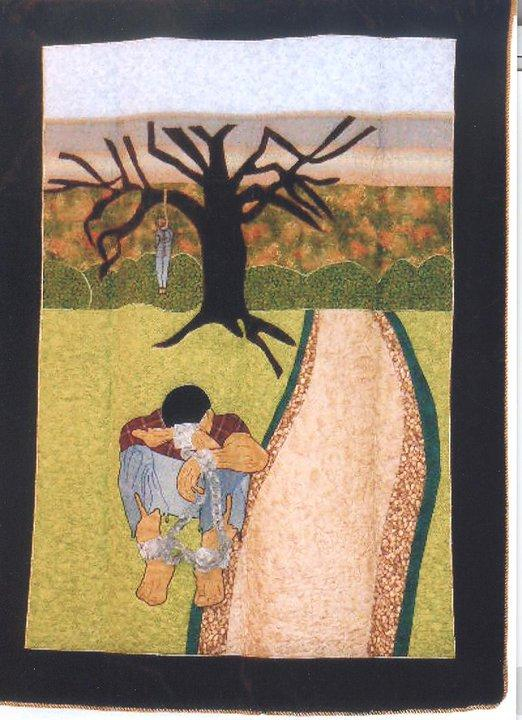

The families worked with archaeologists and volunteers to sift through soil that had been scooped from the floor of a cabin on the Sotterley Plantation.

Gwen Bankins, 61, stood in a hot, cramped cabin in Southern Maryland on a recent afternoon and thought about the lives that had passed through it.

Nearly 180 years ago, her great-great-grandfather — Hilry Kane, an enslaved man, was sold on an auction block. The price: $600.

He was allowed to live with his wife and children in the tiny, one-room cabin on a sprawling tobacco farm, known as the Sotterley Plantation, about 60 miles from Washington in St. Mary’s County.

Now, Bankins occupied that same space — and she wasn’t alone.

A few feet from her in the cabin, stood John Briscoe Jr., 64, whose great-great grandfather had owned Sotterley — and the enslaved people who worked and lived on the grounds — for years.

The two had come together that day to help a team of archaeologists from St. Mary’s College of Maryland and volunteers carefully dig and sift through buckets of soil that had been scooped from a two-foot-deep hole in the cabin’s dirt floor. They hoped to find bits of artifacts that would offerclues aboutwhat life had been like for those who lived there and shed light on the region’s history.

“This is a shared experience,” Bankins said. “We are both here because our ancestors survived. We have to learn it and share it.

Learn how the site has survived to depict American history.

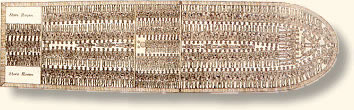

Our digital gallery about the enslavement sheds light on the experienced by people like Hirly Kane.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.