Who Was the Unsung Hero of the 1964 Civil Rights Act?

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., The Root

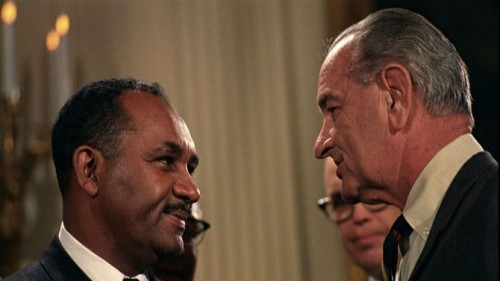

Fifty years ago this Wednesday, July 2, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act into law at the White House. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and a bevy of politicians crowded around him, taking in the historic moment, as significant as any in advancing American race relations since the end of the Civil War. Although the struggle for voting rights would continue for another year (and beyond), the 1964 Civil Rights Act dealt a severe blow to Jim Crow-style segregation in public schools and accommodations. At least as a matter of law, it forbade forevermore discrimination based on “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” It was, as Sen. Everett Dirksen famously quoted the writer Victor Hugo, “an idea whose time [had] come.” But it was anything but inevitable.

Unfortunately, since then, we’ve had to endure the long and silly debate over which man deserves more credit for the bill’s passage through the House and Senate en route to the president’s desk: Johnson, the political animal inside the White House, or King, the charismatic civil rights leader at the forefront of the march outside it. The fact is, both men were critical. And by setting up the debate in this way, we not only distort the complexity of such an undertaking, but we also dangerously reinforce the notion that when it came to getting things done during the civil rights movement, the insiders were white and the outsiders were black. Nothing could be further from the truth, especially where the 1964 Civil Rights Act is concerned.

Just as vital to the bill’s success was another African-American leader. Another “Jr.,” he was far less well-known, precisely because he was so deep inside the process. His name was Clarence M. Mitchell Jr., and he was the chief Washington lobbyist for the NAACP during the extraordinarily heroic phase of the civil rights movement.

As far as I’m concerned, Mitchell was and remains the unsung hero of the 1964 law. You won’t see his face in many pictures. His focus was on the law and the finesse needed to ensure that the bill had enough votes to pass. Although the law has been studied and discussed in great detail over the past half-century, thankfully new works continue to shed light on it and its pivotal players. For giving Mitchell his due, we owe a debt to Todd Purdum, author of this year’s masterful anniversary account, An Idea Whose Time Has Come: Two Presidents, Two Parties, and the Battle for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As soon as I read Purdum’s book, I knew I wanted to dedicate my column on the Civil Rights Act to Mitchell.

Read the full article here.

Read more breaking news here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.