This Date in History: The Wilmington Massacre of 1898

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

From Equal Justice Initiative

In the late 1890s, Wilmington, North Carolina, a port city between the Atlantic’s barrier islands and the banks of the Cape Fear River, became an island of hope for a new America.

Residents of the city’s thriving Black community made themselves a political force, exercising the rights of citizenship guaranteed to them after the Civil War by the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. Across the South, such activity had triggered deadly white violence against Black voters, organizers, and officeholders in the decades since the war. But in Wilmington, a city of 20,000, the votes of 8,000 Black men helped a rare biracial “Fusion” alliance elect candidates of both races.

Three of the 10 aldermen were Black. The city had Black health inspectors, postmasters, magistrates, and policemen, albeit under orders not to arrest anyone white. The county coroner, jailer, and treasurer were Black, as was the register of deeds. Black business people pooled their money in three Black-owned banks. Families a generation removed from enslavement owned their homes and read a local Black newspaper.

As modern-day Wilmingtonian Tim Pinnick, a genealogist, put it, “Things functioned the way they were meant to function as a result of Emancipation.”

Planning a Coup

But if Wilmington looked to some Americans like a model for the South, powerful white leaders, including the president of Wilmington Cotton Mills Company, the editor of the Raleigh News and Observer, and the chairman of the state Democratic party, could not abide it. They set out to topple what the newspaper editor labeled “Negro rule.”

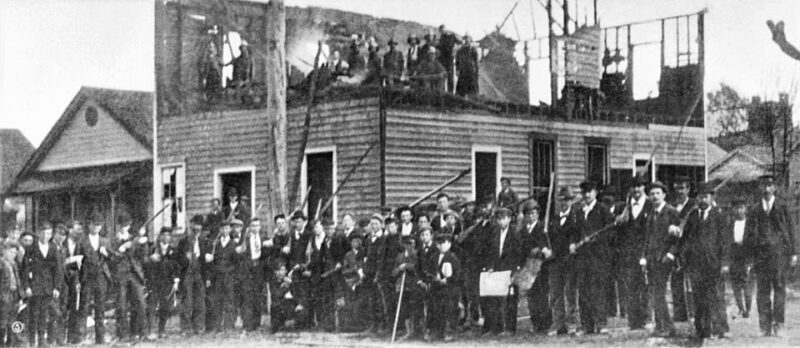

One hundred and twenty-five years ago, on November 10, 1898, a shocking coup d’etat was executed.

The plotters had set the stage by creating what they called the “White Supremacy Campaign.” They printed falsehoods about Black men preying on white women and stockpiling guns. They targeted the Fusion officeholders and the Black newspaper, summoned militias and white vigilantes known as Red Shirts, and terrorized Black voters at the polls.

“If you see the negro out voting tomorrow, tell him stop,” one of the leaders, former Confederate Colonel Alfred Moore Waddell, told a gun-waving white audience on the eve of Wilmington’s 1898 election. “If he doesn’t, shoot him down. Shoot him down in his tracks.” Mr. Waddell vowed to “choke the current of the Cape Fear River” with Black bodies if he had to.

On November 10, Red Shirts, militiamen, and white mobs surged through Wilmington’s streets and massacred 60 or more Black people.

Read more about those who gave their lives to vote in the Wilmington race riot. You can also watch American Coup: Wilmington 1898 or discover the timeline of events on PBS.

Our virtual galleries reveal more Black history, including those exhibits about Reconstruction, a brief period when Black politicians took office.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.