The City Where the Summer of 2020 Never Really Ended

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Molly Olmstead, Slate

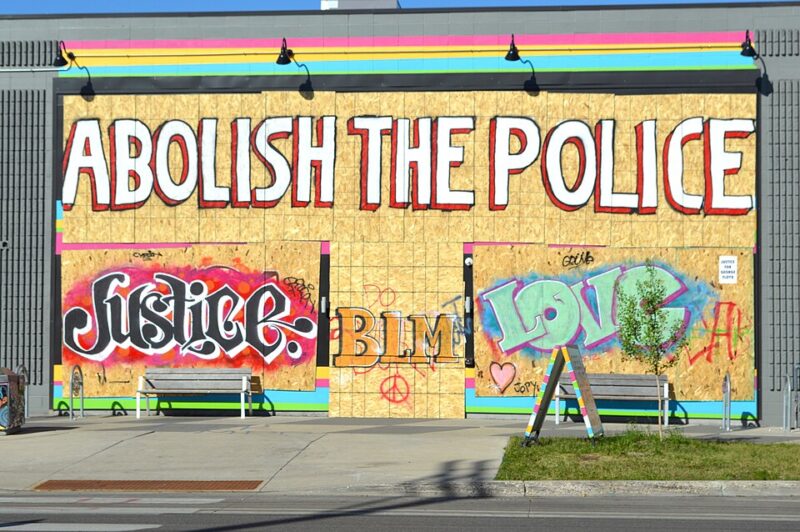

Five years after the murder of George Floyd, his death is still a defining feature of the mayoral race.

Looking back at the political career of Minneapolis’ Mayor Jacob Frey, one moment stands out. It was June 6, less than two weeks after the murder of George Floyd, and Frey had emerged to talk to a crowd that had gathered near his home. In the video, he seems small and almost boyish in his baseball shirt and “I CAN’T BREATHE” mask, his shoulders somewhat slumped, unheard over the fury of the crowd. A woman speaking with a microphone asks Frey if he will commit to defunding the police department.

“It’s important that we hear this,” she says. “Because if y’all don’t know, he’s up for reelection next year. And if he says no, guess what the fuck we’re going to do next year?”

After Frey responds, saying in a muffled voice that he does not support the full abolition of the police, the protesters shout him down, and he is driven out of the crowd with chants of “Go home, Jacob, go home!” and “Shame! Shame!”

For a man once considered a darling of the Democratic Party, it was a remarkable moment, and one that seemed indicative of just how seismically the party’s politics had shifted. It seemed hard to imagine, in that moment, that Frey could bounce back. And yet, this week, Frey is headed toward his second election since then, with more power in the city than ever before, that display of public scorn a distant memory.

Five years on from the police killing that upended the country, it is tempting to feel like the U.S. has completely moved on from George Floyd. The last presidential election ushered in an era of conservative reactionary politics in which all talk of revolutionary racial justice has been thoroughly obliterated; cities now worry not so much about police bias as about masked federal agents snatching Latinos off the street or National Guard members descending to quash democratic protests. In Minneapolis, the site where it all began, not a single major mayoral candidate supports cuts to the police department. The movement to defund the police feels in many ways long dead. And yet, if you take a closer look at Tuesday’s mayoral race, a contentious fight between two Democrats, the echoes of 2020 are still there, a significant part of the fight over the city’s character.

On Tuesday, Frey faces his first serious challenge. Frey emerged from that summer of protests as an entirely different and, some would say, calculating figure, having used centrist anxieties to wrest governing power from the City Council. His main challenger, Omar Fateh, a democratic socialist, has built a campaign on frustrations from the left, promising to rid the city of Frey’s corporate-friendly liberal politics, the kind of politics that sounded nice and social justice–friendly but ultimately held the city back from more radical action after Floyd’s murder. As a result, polls show Fateh in striking distance. It’s a new political fight in Minneapolis, with the city’s first chance in recent memory to have its own lunge toward the socialist left.

But if you talk to people who know the city, they’ll tell you that this is not Minneapolis’ Zohran Mamdani moment; it’s not a matter of a fresh new start. Instead, they say, it’s a moment to look back at just how much the city continues to be weighed down by the anger and pain of that contentious summer.

Discover how Floyd’s murder impacted Frey’s politics, how his opponents are responding, how people discuss the issue of police, and why some people accuse democrats of moving on from defunding the police.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.