Special News Series: Rising Up For Justice! – Black Portland reflects on role of white allies in movement

Share

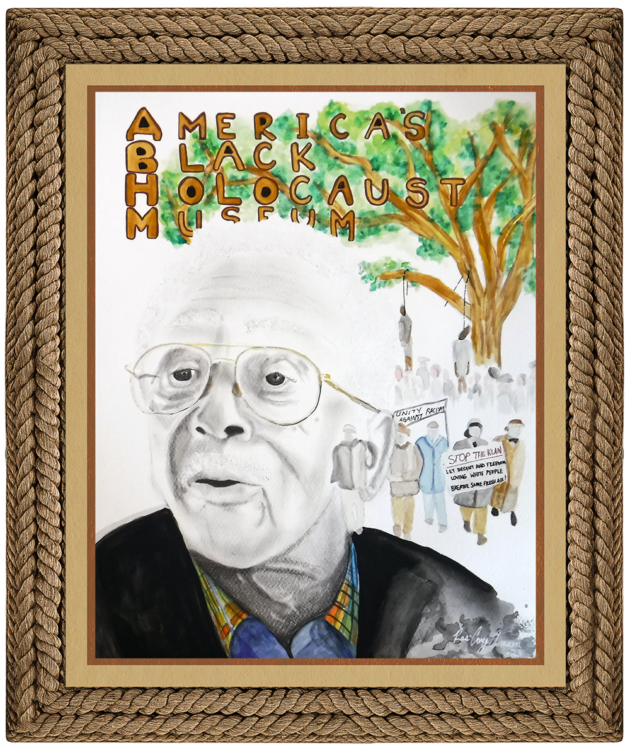

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Introduction To This Series:

This post is one installment in an ongoing news series: a “living history” of the current national and international uprising for justice.

Today’s movement descends directly from the many earlier civil rights struggles against repeated injustices and race-based violence, including the killing of unarmed Black people. The posts in this series serve as a timeline of the uprising that began on May 26, 2020, the day after a Minneapolis police officer killed an unarmed Black man, George Floyd, by kneeling on his neck. The viral video of Floyd’s torturous suffocation brought unprecedented national awareness to the ongoing demand to truly make Black Lives Matter in this country.

The posts in this series focus on stories of the particular killings that have spurred the current uprising and on the protests taking place around the USA and across the globe. Sadly, thousands of people have lost their lives to systemic racial, gender, sexuality, judicial, and economic injustice. The few whose names are listed here represent the countless others lost before and since. Likewise, we can report but a few of the countless demonstrations for justice now taking place in our major cities, small towns, and suburbs.

To view the entire series of Rising Up for Justice! posts, insert “rising up” in the search bar above.

By Gillian Flaccus, Associated Press

More than two months of protests in one of the whitest major cities in America have prompted deep introspection in Portland, Oregon’s small Black community about the role of white protesters in the Black Lives Matter movement

PORTLAND, OR. — More than two months of intense protests in Portland, Oregon — one of America’s whitest major cities — have captured the world’s attention and put a place that’s less than 6% Black at the heart of the conversation about police brutality and systemic racism.

Since May, nightly demonstrations in Oregon’s largest city have featured overwhelmingly white crowds — from middle-aged mothers marching arm in arm to the mayor getting tear-gassed by federal agents to teenagers dressed in black smashing police precinct windows and tossing fireworks at authorities.

The weeks of often-chaotic protests have transformed Portland into a microcosm of the national debate on race and police brutality. It’s also prompted introspection in the liberal city’s small Black community about the role of white demonstrators in the Black Lives Matter movement and what it means to be a white ally in this transformational moment.

The violence and vandalism that have marked the protests, often done by white people, have divided the Black community, along with a debate over what’s next. Some want to keep marching, while others want to use the momentum to work with elected officials on cementing long-term change.

“It’s a perfect storm with everything that’s been happening, and add to that the attention of the world being on Portland, Oregon, right now — we have a unique space,” said Sam Thompson, who founded the group Black Men and Women United last month to push the movement toward long-term Black resilience.

“If those people weren’t there and they weren’t protesting to the level they are now, we wouldn’t be having this conversation 2 1/2 months later,” he said. As white people see the protests, “when the person that looks like you is breaking the windows and starting the fires, you deal with that a lot differently than when it’s someone who doesn’t look like you.”

Portland’s movement has carried a current of tension as the Black community and white protesters navigate a complex racial calculus: In such a white city, how can white residents support Black rights without making themselves the story?

That’s a delicate question in a progressive city with a deeply racist past. Portland, a focal point of the Black Lives Matter movement in part because of its bastion of white supporters, is so lacking in diversity because of centuries of laws that excluded and marginalized Black people.

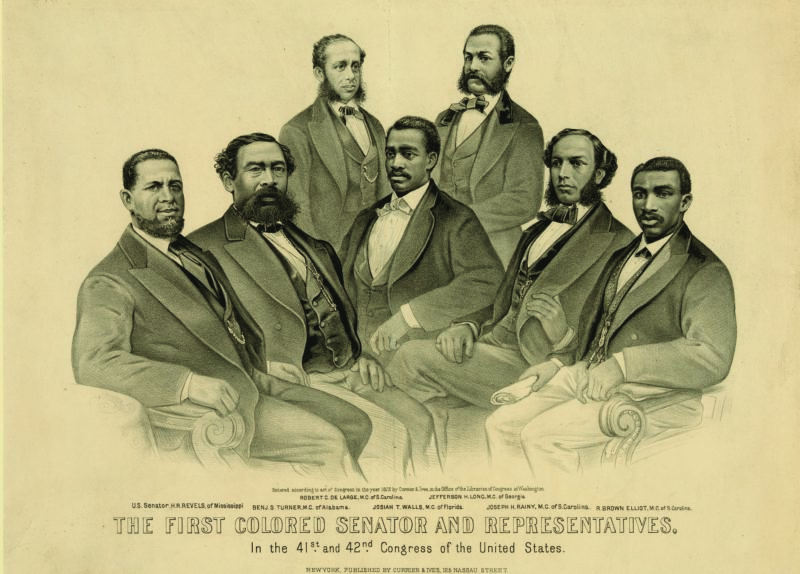

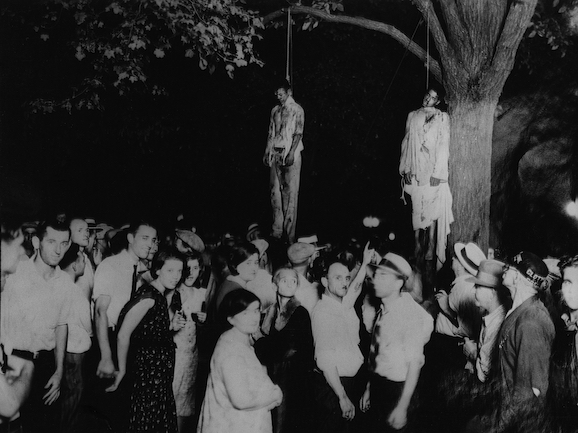

Early “exclusion laws” prohibited Black people from settling in Oregon, and by the 1920s, Portland was known as one of the most segregated cities north of the Mason-Dixon line and a hotbed for the Ku Klux Klan. Later, real estate laws and city planning effectively crammed Black families in a few pockets of Portland. Today’s soaring real estate prices have scattered those Black homeowners to the fringes of the city and beyond.

“We do not have an area that’s ours, and that was intentional,” Thompson said. “These are the things we’re trying to work through.”

Because of that history, some Black people have felt a cognitive dissonance when they see the crowds of white supporters, many of them arriving from homes in neighborhoods that were once Black havens.

“We live in a state that was designed to be a white utopia, and it is truly something remarkable for Portland currently to be at the center of the nation’s attention for Black Lives Matter,” said Cameron Whitten, founder of the Black Resilience Fund, which has raised $1.5 million this summer to invest in the Black community. “I could disagree with how they’re doing it, but in the end, they’re putting their bodies on the line to protect me — and that is huge compared to what we’re used to.”

While many Black residents have embraced that enthusiasm, the white crowds make retaining ownership of the movement critical. That’s led to disagreements in the Black community about what it means to be a white ally.

Some, including the former leader of the Black United Front and the head of the local NAACP chapter, have criticized white protesters who vandalize police precincts amid their call to defund police. Some Black leaders also held a news conference with Mayor Ted Wheeler — the wealthy white scion of a timber family — to say violence is distracting from the Black Lives Matter message.

Those appeals from “gatekeepers” in the Black community have angered some Black activists, who say that level of protest is necessary to keep the pressure on elected officials and pales in comparison to the violence white people have done to Black people.

“Why would I give a (expletive) about property when we’re talking about people that are losing their lives?” said Teressa Raiford, who experienced racism growing up in Portland and founded Don’t Shoot PDX, an organization pushing to defund police.

“That is outrageous, and it’s happening in 2020. That’s incredible that that would happen, and the world would view that and talk about the damage on the sidewalk or on a building,” she said.

Raiford was among those who grew alarmed when the telegenic Wall of Moms, a group of middle-aged, mostly white women, rocketed to national attention as they marched arm in arm at the nightly protests. Media flocked to their story, but the group imploded within days over accusations that their white founder wanted to monetize the group and weaponize it against President Donald Trump.

A smaller number of the self-described moms still protest, joining Black mothers under the group Moms United for Black Lives. They are led each night by Demetria Hester, a Black activist who was attacked three years ago by a white supremacist, which some believe set the stage for the city’s current racial reckoning.

Hester, who was arrested this week while protesting, said the white moms have impressed her with their commitment to “getting woke” — educating themselves about Portland’s racist history and the extent of their privilege as white Americans.

“They’re working hard to educate themselves and educate other people and help the Black community. Our moms are wonderful for even acknowledging the fact that they have white privilege and the system needs to change,” she said after prosecutors dismissed her charges.

“They’ve been arrested, they’ve been tear-gassed, they’ve been hit with rubber bullets,” she said of the white moms. “They’re going through just like what we’re going through — and that opens their eyes to a whole other level of understanding.”

Read the full article here.

Unfortunately, many white people are afraid of backlash if they support Black lives.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.