‘Last Seen’: After slavery, family members placed ads looking for loved ones

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Maureen Corrigan, NPR

In 2017, historian Judith Giesberg and her team of graduate student researchers launched a website called Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery. It now contains over 4,500 ads placed in newspapers by formerly enslaved people who hoped to find family members separated by slavery. The earliest ads date from the 1830s and stretch into the 1920s.

Giesberg says that when she’s given public lectures about this online archive of ads, the audience always asks “the“ question: “‘Did they find each other?'” Giesberg writes:

I always answer the question the same way. And no one is ever satisfied with it. “I don’t know.”

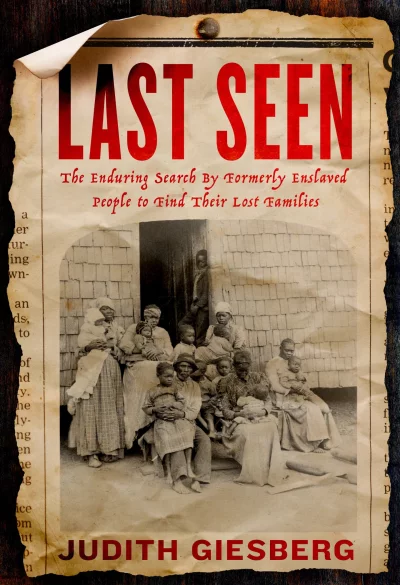

Giesberg’s new book, called Last Seen: The Enduring Search by Formerly Enslaved People to Find Their Lost Families, is her more detailed response to the question. In each of the 10 chapters here, she closely reads ads placed in search of lost children, mothers, wives, siblings and even comrades who served in the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War.

Giesberg isn’t trying to generate reunion stories. Although there are a couple of those in this book, Giesberg tells us the cruel reality was that: “The success rate of these advertisements may have been as low as 2%.”

Instead of happy endings, these ads offer readers something else: they serve as portals into “the lived experience of slavery.” For instance, countering the “Lost Cause” myth that enslaved people were settled on Southern plantations and Texas cotton fields, the ads, which often list multiple names of white “owners” as a finding aid, testify to how Black people were sold and resold.

Keep reading to learn which ads hit the hardest.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.