How the 14th Amendment’s Promise of Birthright Citizenship Redefined America

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Martha S. Jones, TIME

When the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified on July 9, 1868 —150 years ago this Monday — it closed the door on schemes that aimed to make the U.S. a white man’s country. It was a victory that was a long time coming.

The ratification of the 14th Amendment in July 1868 transformed national belonging, and made African Americans, and indeed all those born on U.S. soil, citizens. Isaiah Wears, a veteran of the abolitionist movement, explained shortly after its passage the rights that he and other African Americans expected to thus enjoy: not only the right to vote and to select representatives, but also “the right of residence….”

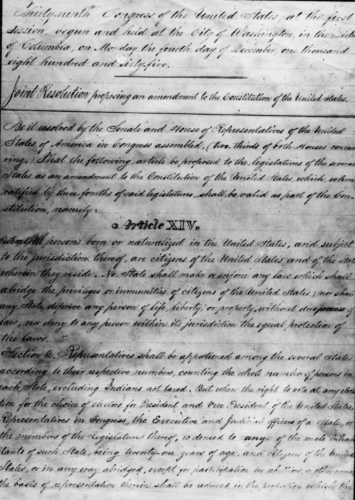

Dramatic events made it possible for birthright to gain a full hearing. The Civil War and the emancipation of some four million slaves moved the issue to center stage in Congress. There, lawmakers worked with a long view in mind, asking who African Americans would be before the Constitution going forward. The first answer came in the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which provided: “All persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States.” Birthright citizenship became law.

More, however, was necessary. Some worried that a mere act of Congress was vulnerable to future lawmakers who might rethink the question and amend the law. Others opined that Congress might not have the authority to define citizenship at all. The remedy for these uncertainties was a constitutional amendment, proposed by Congress and ratified by the individual states that provided for birthright citizenship. The result was section 1 of the 14th Amendment, ratified in July 1868 and guaranteeing to black Americans — and all people born or naturalized in the United States — the constitutional protection against removal.

Just months later, in January 1869, Isaiah Wears spoke on behalf of African American political leaders from across the country, heralding the advent of an era in which the “right to residence” would be protected. There were many struggles ahead for black Americans over civil and political rights. But one matter was settled. Gone were schemes that proposed to force their removal from the nation.

African American struggles of the 1800s bequeathed to those born in the 21st century the basis for the right to be free from removal, exile or banishment. The terms of the very same 14th Amendment are also today the subject of a new debate, one that asks whether birthright doesn’t too generously extend citizenship to all those born in the U.S. This pre-history of the Amendment reveals how, in the 19th century, when citizenship was loosely defined, racism could determine who enjoyed constitutional rights. Thousands of black Americans were left to live under an ever-present threat of removal. The story of their fight for the “right to residence” is a cautionary tale for our own time.

Read the full article here.

Read more Breaking News here.

View more galleries from the ABHM here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.