Free Mandela (from the Prison of Fantasy)!

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Robert Mackey, The Lede in the New York Times

As the celebration of Nelson Mandela’s life continues, some writers who lived through the anti-colonial period in Africa have suggested that it is important to make sure the real historical context for his achievements is not obscured by myths that smooth out the rough edges of the recent past.

A good place to start is with a blog post on the London School Economics website written by Thandika Mkandawire, who was jailed for his role in the struggle for the independence of Malawi and spent 30 years of exile. Mr. Mkandawire writes:

In this brief note, I will simply point to the influences the man had on my generation (politically speaking). For much of the last century during which I grew up, Africa was involved in ridding itself of colonialism and racist rule. From the 1960s onwards, the walls of colonial domination crumbled one after another as the colonialists granted independence or simply ran away as did the Belgians while ensuring that King Leopold’s ghost would continue to haunt the heart of Africa that Congo is. And so for my generation, the death of Mandela marks the triumphant end of Africa’s liberation struggle.

[…]

Another author dealing with the subject is the South African journalist and New Yorker Tony Karon, who just republished an essay he first posted on his blog in 2005 under the headline, “Free Mandela (From the Prison of Fantasy)!” Mr. Karon’s essay, now titled “Three Myths about Mandela Worth Busting,” begins:

I sometimes feel Nelson Mandela is in need of rescuing, trapped in some pretty bizarre narratives that have nothing to do with his own story or politics. Full disclosure: I freely admit that Nelson Mandela is the only politician for whom I’ve ever voted; that I celebrate him as a moral giant of our age, and that I proclaimed him my leader (usually at the top of my tuneless voice, in badly sung Xhosa songs) during my decade in the liberation movement in South Africa. That’s maybe why the “Mandela” I’ve encountered in so much American mythology is so unrecognizable.

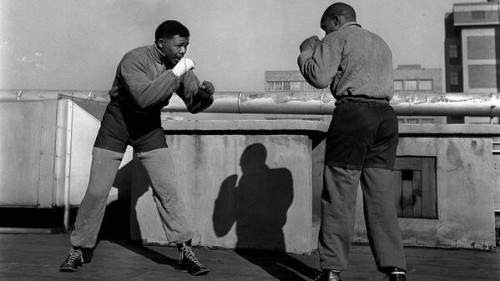

The three myths Mr. Karon sets out to destroy are: that Mr. Mandela was a pacifist; that only his singular personality prevented a race-tinged bloodbath in post-apartheid South Africa; that the struggle against apartheid was itself driven by a kind of black nationalism which allowed no role for white activists.

[…]

Another of the authors is Alain Gresh, deputy director of Le Monde Diplomatique, who tackled the myth-making around Mr. Mandela in a 2010 article headlined, “When Mandela Wasn’t the Messiah,” that looks at the Cold-War context of the anti-colonial liberation struggles across Africa.

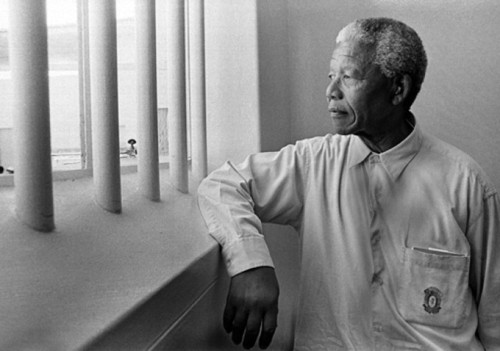

Watch a rare video of Nelson Mandela working in the prison yard in 1977.

For a detailed and thoughtful outlining of myths and facts, read the full article here.

Read more Breaking News here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.