Building a Black Male Pipeline Into Public Education

Share

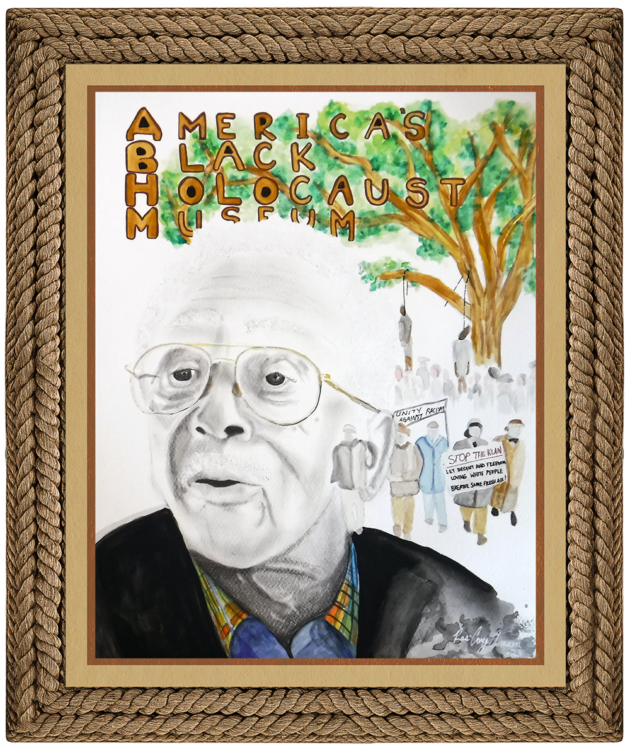

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Aziah Sid, Word in Black

Nearly 900 Black male educators came together in Philadelphia to dialogue about how we get — and keep — them in teaching.

South Side of Chicago-native Abdul Wright, grew up the oldest of several siblings. His family moved through low-income housing — at one point they found themselves in a homeless shelter.

But Wright, who was named 2016 Minnesota Teacher of the Year, is a prime example of how an excellent education positively changes the outcome of a Black man’s life in America.

“I have students who I see in newspapers that get killed. I have young people who don’t know what they’re about to do for the next week of their life,” Wright said. “Its triggering for me because it reminds me of my childhood, and I can’t save them.”

He was one of nearly 900 Black male educators gathered in Philadelphia for the fifth annual Black Men Educators Convening, which was sponsored by the Center for Black Educator Development, a national nonprofit founded by veteran Philadelphia educator Sharif El-Mekki.

Since 2019, the organization’s worked to, as its website says, boost “the number of Black educators so that low-income Black and other disenfranchised students can reap the full benefits of a quality public education.”

“Innovation,” “brotherhood,” and “Black excellence” were some of the words used by Wright, and other panelists and attendees — teachers, executives, education advocates, and others — as they discussed the importance of building intergenerational relationships, the unsung sacrifices educators make, and how to ensure the next generation of Black boys want to become teachers.

But from a lack of classroom resources to poor working conditions and racism on the job, there are significant barriers to ensuring Black people join the profession and stay in the classroom.

Keep reading to learn about these barriers.

Black educators often leave the field after struggling with stress.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.