Black Spirituals as Poetry and Resistance

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By: Kaitlyn Greenidge, The New York Times

These songs — the oldest musical expressions of the slave experience in this country — still have a lot to teach us about how we think about death and dignity.

Many of the people I interviewed were members or descendants of the Great Migration, the movement of more than six million Black Americans from the rural South to the country’s Northeast, Midwest and West beginning in 1916. These were people in their 60s, 70s and 80s. They or their parents had come to New York City in the first wave of migration, before World War II. This particular section of Brooklyn, then, was still so connected to history that certain blocks could trace their lineage to particular sections of North Carolina, Virginia and Georgia. Sometimes someone would say, “I was different growing up, because we came from South Carolina.”

Despite this, they were all united around a certain understanding. During my oral-history sessions, when I asked an elder about a person they were talking about, I would say gracelessly, “So, when did they die?” There would be a pause in the conversation — an intake of breath from whomever I’d posed the question to — as if I had reached out and pinched them. My boss, a much more skilled oral historian than I, would gently correct me: “When did they pass?” The conversation would then resume. When we spoke to white historians about the work we were doing — documenting the history of a community-led historic preservation project — we used the word “died” interchangeably. There was never the same pause.

It’s a fact of American life that the divide between Black and white affects us from the cradle to the grave. The differences in race coil through even our most intimate moments, into our psyches, even in how we conceive of death. “Passed,” “passed over,” “homegoing,” “sunset service,” “transitioned” — these are the words and euphemisms we use to describe an end to a life, to maintain a sense of personhood in a world that would take that from us even in death.

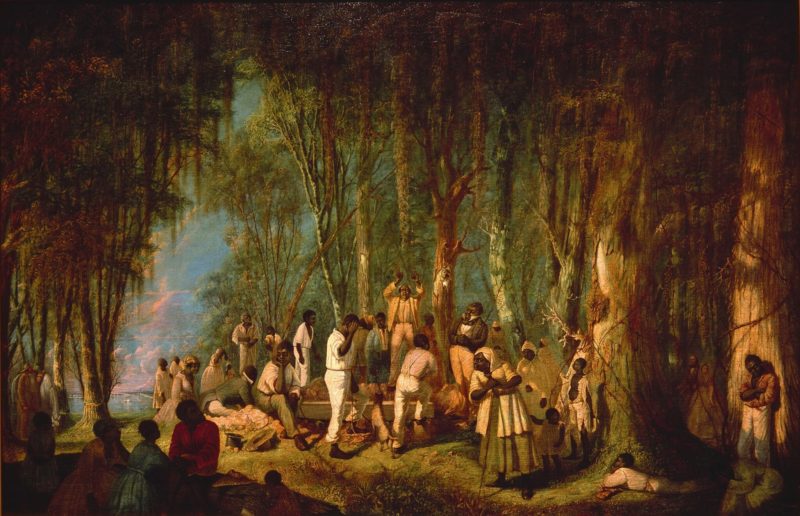

This imaginative leap is most on display in spirituals. These are the songs, born from rhythms of stolen labor, that enslaved Black people invented on the plantations. They are an early instance of the kind of doublespeak and double consciousness made famous by W. E. B. DuBois. They served, on the one hand, as a testament to the Christian experience but also, on the other, as a way to articulate a resistance to slavery. Spirituals, like many other musical genres across the African diaspora, draw on traditions from West Africa. But spirituals are unique to the experience of the enslaved in the United States — the same artistry and craft that birthed them here produced recognizable, but decidedly different, music across the Caribbean and South America.

To learn more about African-American poetry and art, click here and here.

More Breaking News here.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.