How HBCUs Rescued Jewish Professors from the Nazis

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Scholar-Griot: Dr. Fran Kaplan

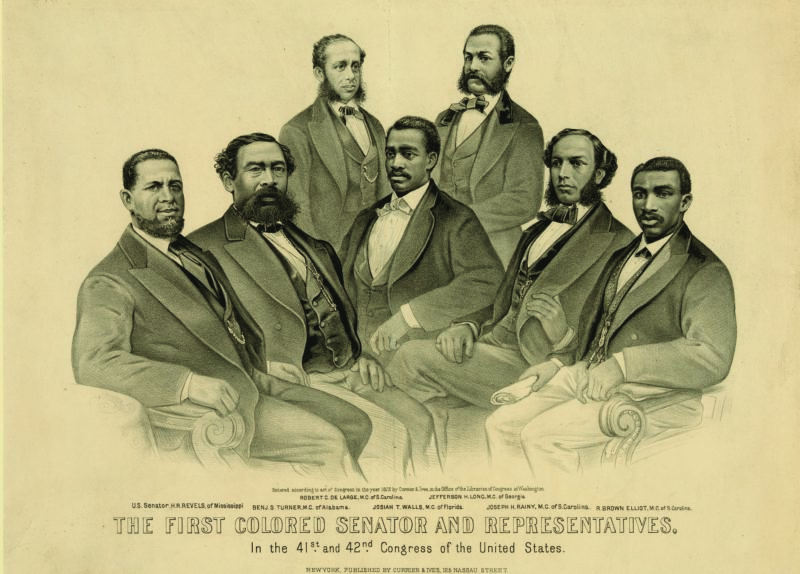

Morgan College faculty, 1948. Photo courtesy of the Beulah M. Davis Special Collections Department, Morgan State University, Baltimore, Md.

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) played a quiet but remarkable role in rescuing Jewish scholars fleeing Nazi persecution in the 1930s–1940s. At a time when many White institutions declined to act, Black colleges stood for humanity.

During years of respect, solidarity, and collaboration, Jewish professors passed on their knowledge and skills to Black students. They also witnessed and experienced personally the oppression that African Americans faced in the Jim Crow South. This story sits at the intersection of racism, antisemitism, academic freedom, and moral courage.

How HBCUs Helped Jewish Professors Survive

In the 1930s, Jewish professors in Germany faced terrible danger. When Adolf Hitler and the Nazis came to power, Jewish people were expelled from universities, stripped of their rights, targeted for violence, and sent to concentration camps. Many professors had to escape Europe to save their lives. They hoped to continue teaching in the United States.

However, most American colleges refused to hire them.

At the same time, Black Americans were living under Jim Crow discrimination and racial terrorism. Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were underfunded and excluded from white academic networks. Yet these same schools made a powerful and brave choice: they opened their doors to Jewish refugee scholars when many others would not.

This decision saved lives—and changed American education.

Closed Doors at White Universities

Even though Jewish refugee professors were highly educated, many top U.S. universities rejected them. Some schools used (secret) quotas to limit Jewish faculty and students. Others claimed there were “no open positions,” even when departments needed teachers. University leaders feared backlash from angry donors and wanted to avoid controversy. As a result, many Jewish scholars in the US were left unemployed and more vulnerable to antisemitism.

Why HBCUs Said Yes

HBCUs understood discrimination deeply. Their presidents and faculty lived under racism every day. They recognized that Nazi antisemitism was another form of racial hatred—similar to white supremacy in the United States.

HBCUs also needed skilled professors, especially in science, medicine, and social sciences. Hiring refugee scholars helped both the schools and the scholars survive.

With help from international rescue organizations, HBCUs quietly hired Jewish professors who had been fired in Europe. These schools did not have much money, but they acted with courage and compassion.

Ernst Borinski and his students in the social science lab at Tougaloo College, circa 1960.

Professor Ernst Borinski at Tougaloo College

One of the most well-known refugee professors was Ernst Borinski, a Jewish sociologist from Germany. After escaping the Nazis, Borinski found a teaching job at Tougaloo College in Mississippi.

Mississippi was one of the most discriminatory states in the country. Still, Borinski believed that education could challenge injustice. He organized discussion groups that brought together Black students, white ministers, journalists, and community members. These meetings were rare and risky in the Jim Crow South. Professor Borinski's interracial dialogue groups were called the Social Science Forums.

These forums provided a rare and "safe space" for open, honest discussions about controversial and critical social issues during the early Civil Rights era. They attracted large, integrated audiences from both on and off campus, and were one of the few places in the segregated South where interracial groups could gather on a basis of full equality. Borinski would specifically instruct his Black students to sit among the White guests to encourage genuine interracial dialogue.

Borinski taught his students that racism and antisemitism were connected systems. He compared Nazi race laws with segregation in the United States. He encouraged nonviolent direct action and helped prepare students for the dangers they would face. Many of his students later became civil rights leaders. His work helped prepare the ground for the Mississippi Freedom Movement.

Photo of Donald and Lore Rasmussen alongside a news article and receipt for a $28 fine paid after Lore was arrested for dining with Louis Burnham in a Black café.

Professors Don and Lore Rasmussens at Talladega College

In 1942, Don and Lore Rasmussen moved to Alabama’s Talladega College, where Don taught sociology and economics and Lore teacher education. Lore was Jewish refugee from Germany. Their first year they were jailed by the Birmingham police for dining with the Executive Director of the Southern Negro Youth Congress in Nancy's Cafe, a Black restaurant. They had violated Birmingham's segregation codes prohibiting Blacks and Whites from dining together without a "seven foot high separation wall."

They were charged with "incitement to riot" and violating Birmingham's segregation codes. They spent a night in the city jail and paid a fine of $28. Lore Rasmussen was freed to leave first. However, she had to stay with her husband in jail since she was not allowed to ride home alone with a Black student. They were eventually bailed out by a Black dentist. Don and Lore became committed "foot soldiers" in the early civil rights movement.

Professor Victor Lowenfield

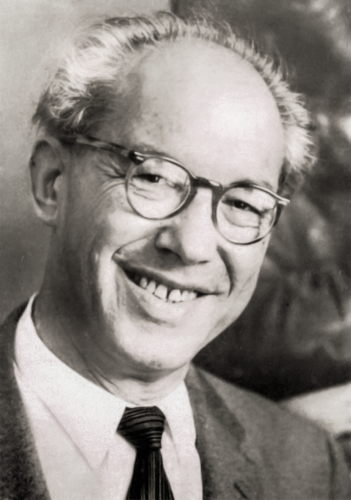

Professor Victor Lowenfeld at Hampton Institute

Dr. Lowenfeld, an elementary and high school teacher, was trained as both an educator and an artist. In 1938 he fled from his native Austria to England before arriving in the United States. Lowenfeld joined the HBCU Hampton Institute in Virginia in 1939 as a professor of Industrial Arts, studio art teacher, and later Chair of the Art Department. In 1945 he was named curator of the distinguished collection of Black African Art there.

Lowenfeld transferred to The Pennsylvania State University (a White public university) as a professor in 1946. He became the Chair of Art Education and stayed in this position until his death in 1960.

Dr. Lowenfeld’s most famous student at Hampton was John T. Biggers, who became a nationally known muralist. Biggers entered Hampton Institute in 1941 and studied art under Lowenfeld. They kept a very close relationship as mentor and protegé. Biggers’ studies were disrupted, however, when he was drafted into the US Navy during WWII. He later followed Dr. Lowenfeld and resumed his studies at Pennsylvania State University where he received his PhD.

Physicist Albert Einstein speaking to students at Lincoln University in May 1946.

Albert Einstein at Lincoln College

Although Albert Einstein did not teach full-time at an HBCU, he strongly supported Black colleges. In May 1946, Einstein received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Lincoln University (the first degree-granting Black university in the U.S.). In his acceptance speech, he passionately denounced racial segregation, calling it a "disease of white people" and pledging not to be silent about it. “My trip to this institution was on behalf of a worthwhile cause,” Einstein said in his address. “There is a separation of colored people from white people in the United States. That separation is not a disease of colored people. It’s a disease of white people.”

Despite Einstein’s celebrity status, his visit to Lincoln was largely ignored by the mainstream media, which normally covered his activities. His visit marked a rare exception to his self-imposed rule against receiving such honors, but it was an opportunity to highlight his strong commitment to civil rights and anti-racism.

Teaching World-Class Knowledge at Black Colleges

At HBCUs, Jewish refugee professors taught subjects that many Black students had not been able to study before. At Fisk University, refugee philosophers introduced students to European thinkers like Immanuel Kant and modern ideas about democracy and human rights.

At Howard University, refugee scientists strengthened programs in chemistry, physics, and medicine. Black students learned advanced research methods that white institutions often denied them.

The Jewish professors treated Black students as serious scholars. In return, students showed respect and curiosity toward professors who had survived fascism.

Shared Struggles, Shared Lessons

Jewish refugee professors and Black students learned from one another. Professors saw American racism up close. Students learned that fascism was not only a European problem but part of a global system of oppression. Together they challenged false ideas about race, intelligence, and human worth.

Why This History Matters

Stories like this often go untold. In 2014, however, a unique exhibit about this history, Beyond Swastika and Jim Crow: Jewish Refugee Scholars at Black Colleges, toured Black, White and Jewish museums around US.

Remembering matters. This history shows us that institutions with the least power can still act with the greatest courage. It proves that education can be a form of resistance. And it reminds us that Black–Jewish cooperation has deep roots.

Footnotes & Archival Citations

- Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars, Placement Records, 1933–1945.

New York Public Library Archives.

(Documents refugee scholar placements at Howard, Fisk, and Tougaloo.)

- Institute of International Education, Records of European Émigré Scholars, 1930s–1940s.

IIE Archives, New York.

- Tougaloo College Archives, Ernst Borinski Papers.

Tougaloo, Mississippi.

(Correspondence, discussion group notes, and course materials.)

- Howard University, Faculty Appointment Records, 1935–1945.

Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Washington, D.C.

- Fisk University Course Catalogs, 1938–1944.

Fisk University Special Collections, Nashville, Tennessee.

- Einstein, Albert. “The Negro Question.” Pageant Magazine, 1946.

(Einstein’s public statements opposing racism and supporting Black Americans.)

Dr. Fran Kaplan is an adult educator, social worker, and award-winning filmmaker based in Madison, Wisconsin, known for her extensive work with America’s Black Holocaust Museum. With over 55 years dedicated to social justice, she has focused on fighting poverty, advocating for civil rights, and preserving Black history. Dr. Kaplan leads Nurtures LLC, providing training rooted in historical understanding. She is also a published author and producer of acclaimed films and digital anthologies on justice.