Why is America so slow to exonerate the wrongly convicted?

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Mark I Pinsky, The Hill

While the wheels of justice turn slowly, the old aphorism goes, they grind exceedingly fine. Yet, as the civil rights activist Rev. Benjamin Chavis told me almost 50 years ago, “they rarely operate in reverse.”

Back then, I covered Chavis’s post-conviction hearing for the New York Times. Chavis led the Wilmington Ten, whose criminal case became a political cause. Their 1971 arrest for arson and conspiracy followed urban unrest in the North Carolina port city. Armed white vigilantes and Ku Klux Klansmen had attacked the Black community. The United Church of Christ dispatched Chavis to reduce racial tensions.

Chavis and the others found sanctuary in a church during the violence and steadfastly denied the subsequent charges. Testimony from three Black men — one mentally unstable and a convicted felon who later recanted — brought conviction. Most of the 10 sentences involved about 30 prison years.

Despite numerous investigation and trial irregularities, including alleged prosecutorial misconduct, Chavis’s “wheels of justice” proved prescient here: A state judge ruled the Wilmington Ten’s trial was fair and their lengthy prison sentences just in 1977.

[…]

Notwithstanding, in 1978 North Carolina’s politically timid Democratic governor, Jim Hunt, declined to pardon the men (the group’s lone woman’s sentence had completed), or commute their sentences. Instead, he reduced sentences so they would be paroled within 24 subsequent months. Chavis was the last paroled, on Christmas Day 1979.

A year later, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the Wilmington Ten’s convictions. In 2012, Gov. Beverly Perdue issued them a pardon of innocence. Chavis is now a Duke University fellow in environmental justice and racial equity.

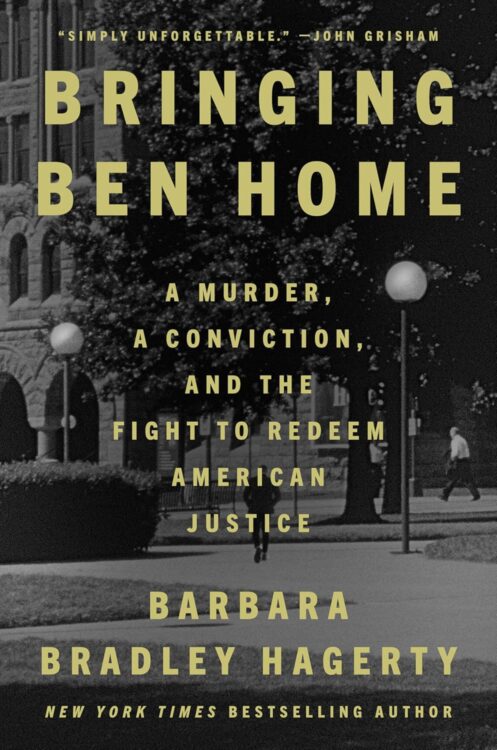

What recalls this past travesty of justice is a new book, “Bringing Ben Home: A Murder, a Conviction, and the Fight to Redeem American Justice,” by Barbara Bradley Hagerty, who for many years covered the Justice Department and religion for NPR.

Related: War on Drugs – or War on Blacks?

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.