I'm A Proud Afro-Latina!

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Scholar-Griot: Melanie Falu

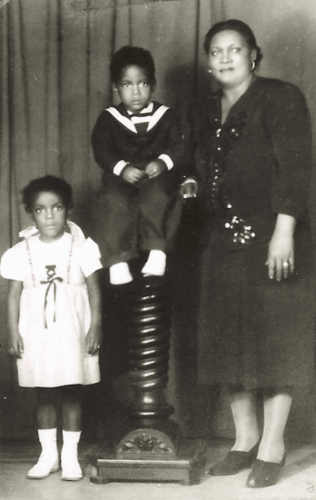

My grandparents - Isabel Navedo and Francisco Alvarez wedding day 1939, Harlem, NY (El Barrio)

My journey as an Afro-Latina started early—really early—and I have my father to thank for how I first learned to see myself. From a young age, he taught me that my skin color wasn’t something to hide—it was something to celebrate. Same with my hair. There was no such thing as “good hair” or “bad hair”—it was just hair, and mine was beautiful. Thanks to him, I grew up knowing how to stand my ground and defend who I am.

What made things harder, though, was needing to defend myself—sometimes within my own family, and then in the wider community too. See, most African Americans deal with prejudice from outside their culture. But as an Afro-Latina, I had to deal with it from both sides.

Some relatives insisted I wasn’t Black, I was Puerto Rican. But anyone could look at me and see that I’m a Black woman. I don’t look like J.Lo, Rosie Perez, or Christina Milian—I’m more Nia Long, Kim Fields, unmistakably Black. And yet even my own mother would tell me, “You’re not Black, you’re Puerto Rican.” My father, on the other hand, made sure I understood the truth: that “Puerto Rico” was a name given by colonizers. The island was originally home to the Borinquen people—the Taíno, who were part of the Arawak group. So I learned early that even the label they gave me wasn’t where I truly came from.

My mother, Ana Alvarez, (age 32) in our living room in the Bronx, NY.

Still, I was surrounded by people—especially family—pushing me to claim an identity that didn’t reflect what the world saw. So when people asked me who I was, I’d say “Puerto Rican” because that’s what was drilled into me. My first experience of being Afro-Latina was basically being told not to embrace my own skin.

And then came the outside world. I’d meet other Puerto Ricans who didn’t know I was one of them—until I spoke Spanish or mentioned my heritage. That’s when the tone would shift: suddenly I was “in.” I remember one friend who told their mom, “Oh no, she’s not morena—she’s Puerto Rican!” And only then did the mom accept me. That stuck with me. If I hadn’t spoken or had someone “vouch” for me, I wouldn’t have been welcomed. That was my first taste of prejudice from my own people.

And on top of that, I still faced the same bias every Black woman in America faces—so I got hit from both sides. What’s wild is that the very things that make up our culture—the music, the flavor, the spirit of being Latina—all have African roots. But the color that represents those roots? People shy away from it. They want the spice but not the skin.

But I was built for this battle. I was taught from day one to defend my truth. I’m not just surviving—I’m thriving. I no longer call myself a Puerto Rican woman first, because when people look at me, they see a Black woman. That’s who I am. My culture is Puerto Rican. My heritage runs deep—I’ve got family born and raised there, I speak fluent Spanish, I vibe to the same rhythms. But I am Black. And I own that, proudly.

I’ll keep educating anyone who doubts that you can be both. Because we are. And it’s time that our own people stop running from the reflection they see in us. Most of us don’t look like J.Lo—we look like Celia Cruz, like Roberto Clemente. That’s us. That’s real. And it’s time we honor that. We’ve been pushed aside—internally and externally—but the fight isn’t over. Education wins. Shaming doesn’t.

This is what it means to be an Afro-Latina. It’s not easy—but it’s powerful.

How Afro-Latinos Came To Be

How Afro-Latinos Came To Be

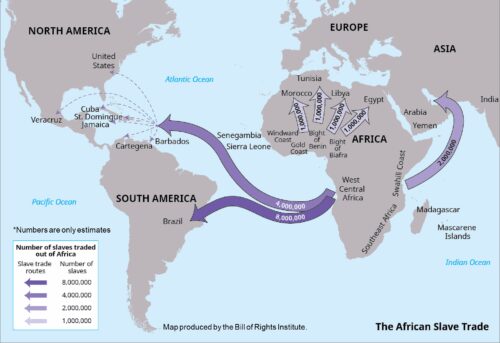

Afro-Latinos are descendants of the formerly enslaved Africans in Latin America and the Caribbean. You probably know about slavery in the United States, but what do you know about slavery south of our border?

Millions of Black Africans were brought as slaves to Central and South America and the islands in the Caribbean Sea. At that time, Spain ruled most countries there, including Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Colombia, and Argentina—while Portugal ruled Brazil and France controlled French Guiana and a few islands in the Caribbean. Naturally, the Indigenous residents of these places had to learn to speak Spanish, Portuguese, or French. So did their African slaves. (Because the Spanish, Portuguese, and French languages came from Latin, Spanish-, Portuguese-, and French-speaking nations in the Americas make up Latin America.)

Slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean was somewhat different from slavery in the U.S. In the Caribbean islands and Brazil, enslaved Africans were often able to hold on to parts of their cultures. For example, they kept African music styles like conga and drumming. They practiced African spiritual traditions and added African flavors to local foods. Dishes like plátanos, alcapurrias, meals wrapped in banana leaves, and Brazil’s feijoada all show this rich history.

Many North Americans assume that people who look Black don’t speak Spanish, Portuguese, or French—or come from Latin America. They are surprised when Afro-Latinas and Afro-Latinos speak fluent Spanish, Portuguese, or French, or celebrate Latin music and food. Few understand how racially diverse Latin America really is. They don’t realize how deeply African cultures shaped Latin cultures.

Melanie Falu's contribution to ABHM reflects not only her professional expertise but also her personal testimony, offering readers a powerful perspective that bridges lived experience with broader social understanding. She is a Certified Professional in Talent Development with more than a decade of experience guiding professionals through transformation in corporate, legal, and technology sectors. With a background in Information Technology Project Management (M.S., NYU Polytechnic School of Engineering) and Social Sciences (B.A., The College of New Rochelle), she specializes in career strategy, adult learning, and change management. Melanie brings to her work a commitment to transparent communication and empowering others to navigate pivotal moments with clarity and purpose.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.