Jim Crow’s Forgotten History of Homicides

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Jennifer Szalai, The New York Times

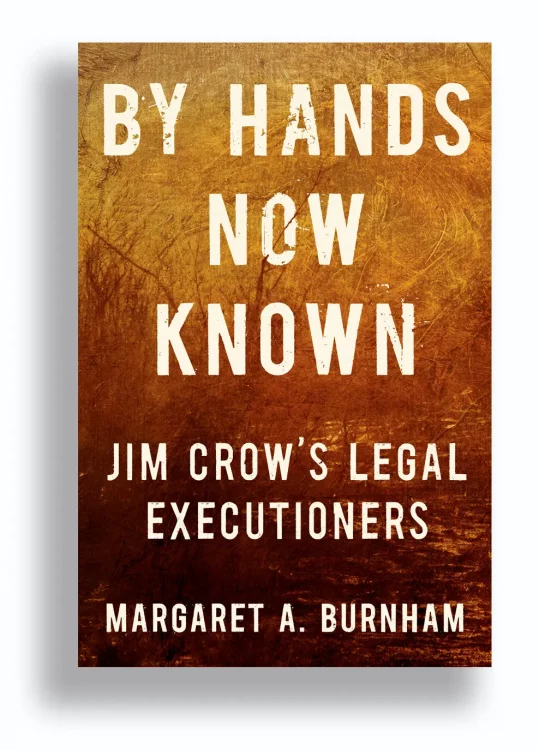

“By Hands Now Known,” by Margaret A. Burnham, examines the chronic, quotidian violence faced by Black citizens in the American South — and the law’s failure to address it.

As far as we know, there are only two surviving documents that account for a death that took place in a jail cell in St. Augustine, Fla., on the evening of Oct. 20, 1945.

One is a death certificate: It states that an “accident” was “caused” by a man “resisting officers of the law,” which led to him “being hit” by an officer with a blackjack. The other is a letter to the New York office of the N.A.A.C.P. from the organization’s St. Augustine branch. The letter describes a man getting bludgeoned to death in front of other detainees, and requests an investigation into the “untimely death of our brother George Floyd whom we believe to have met his death unjustifiably so.”

The discovery of this George Floyd — a Black man who was killed by a police officer 75 years before another Black man with the same name was killed by a police officer — “was not entirely unforeseeable,” Margaret A. Burnham writes in “By Hands Now Known.” More than a decade ago, Burnham, a law professor, founded the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project at Northeastern University, and with the help of the political scientist Melissa Nobles created a database of what Burnham calls a “forgotten history of racially motivated homicides” in the American South during the Jim Crow era. Burnham and Nobles collected whatever information they could find, interviewing descendants to learn about instances of racial violence that had been “largely ignored” in official accounts.

The death of George Floyd in 1945 was one such tragedy. It “destroyed his family,” Burnham writes. The fact that he shared a name with a man who died in analogous circumstances in 2020 speaks to how “quotidian” such violence was — entrapping so many Black Americans in its grip.

Even as more attention finally gets paid to the kind of brazen mob violence that included the lynching of Black people and the burning of entire neighborhoods to the ground, “By Hands Now Known” draws on the research of the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project to do something else. What Burnham seeks to show is the “chronic, unpredictable violence” that shaped daily life in the South — “how lethal, for women and for men, the most commonplace encounters under Jim Crow could be.”

Head to the New York Times for more information.

ABHM’s online gallery includes an exhibit about Jim Crow.

Don’t forget to stop by our breaking news archive before you leave!

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.