Jameson Green Won’t Apologize for His Confrontational Paintings. Collectors Love Him for It

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

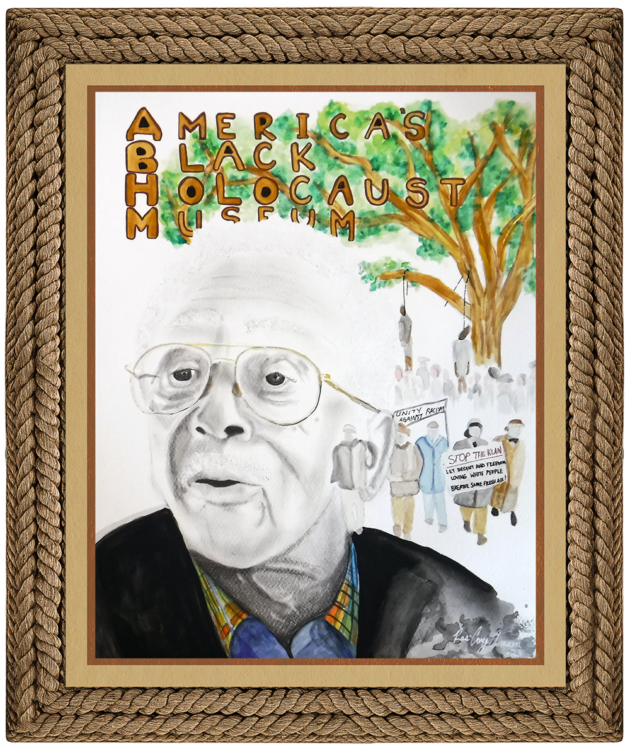

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Zachary Small, Artnet

Prices for his paintings have quadrupled over the past two years as buyers search for art that will challenge them.

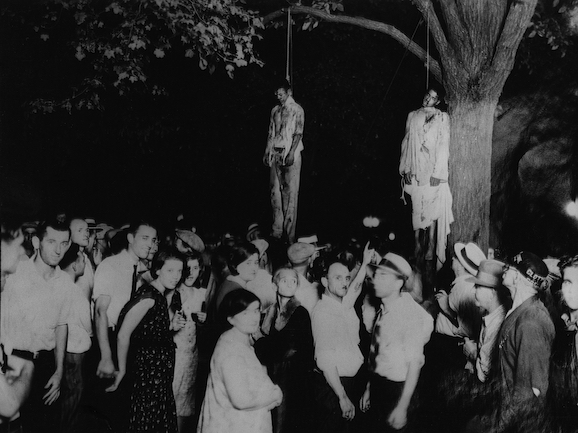

Crucifixion. Cannibalism. Decapitation. A noose hanging from a tree. Jameson Green’s current exhibition at Derek Eller Gallery contains enough violent imagery to send a wandering nun to her rosary beads. Abraham raises a knife to slice his son’s neck. Jesus slumps on the cross wearing a crown of thorns as gray as his face. The Three Wise Men’s heads are depicted piked on trees stubbed with nails.

Every one of these paintings, on view in “With Regards, Without Regards” through October 8, has sold to members of a 300-plus waiting list of collectors clamoring for the work of the 30-year-old artist. His gallery claimed that the average price of a Green painting has quadrupled in just two years from about $7,500 to nearly $30,000. Some paintings have been priced as high as $75,000. Private collectors are eager to buy, competing with cultural institutions like the Dallas Museum of Art and Pérez Art Museum Miami, which have already acquired his work. The numbers are almost certain to keep rising.

Green would prefer to avoid thinking about money, though it provides him the privilege of focusing on his art. Last October, he upgraded from a South Bronx studio to a larger space in Long Island City where his canvases have grown more than 14 feet wide.

“I would love to push the boundaries of painting,” said the 30-year-old artist, who graduated from his MFA program at Hunter College just three years ago after studying with professors like Juan Sanchez. He had trouble finishing paintings back then, so another teacher, Drew Beattie, delivered an ultimatum: work faster than your inner critic or slow down.

He leaned into the frustration, producing autobiographical paintings that combined art-historical references to Francisco Goya, Pablo Picasso, Oskar Kokoschka, and Philip Guston with the singed memories of a difficult childhood and his personal experiences with racism.

Green is a Black man who frequently includes symbols of racism in his paintings, like a klansman’s hood and a cartoon caricature of a dark-skinned boy with thick lips. These elements, he says, are “a representation of corruption in pursuit of power, racial division, bigotry, and through these things personal suffering,” which can make the paintings hard to look at. In one, a boy sits underneath a noose while painting the portrait of a man’s severed head.

Green’s embrace of such difficult material despite the risk of backlash has defined him as someone willing to expose his own vulnerabilities and contradictions. It’s a philosophy he gleaned from the artist Robert Crumb, whose comic books Green often read as a child at the New Haven public library in Connecticut.

Learn more about Green and his work.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.