My First Visit to ABHM

Share

About ABHM

Explore Our Galleries

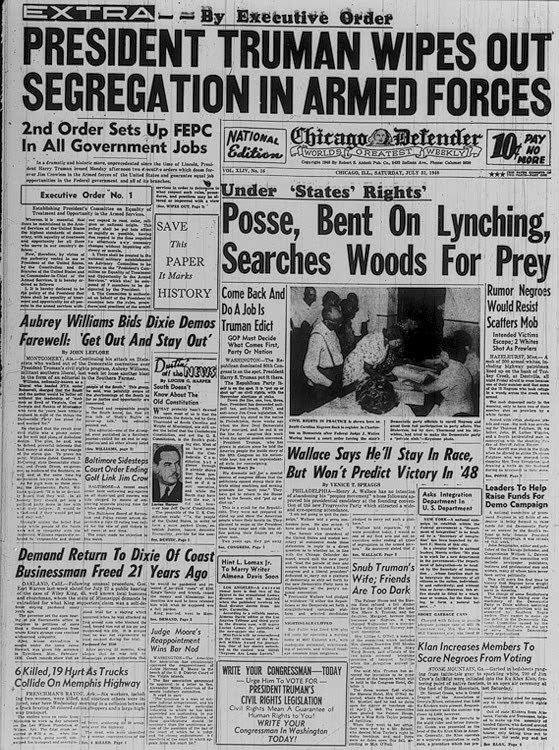

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

GRIOT: Richard Prestor, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

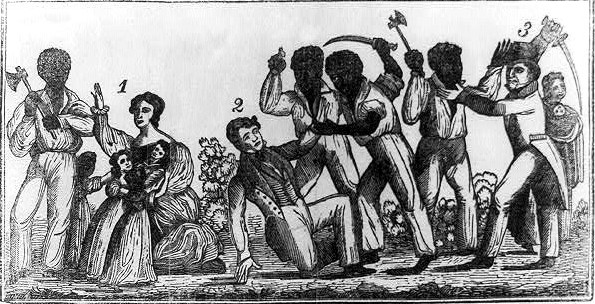

An article in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel announced the opening date of a new museum: America’s Black Holocaust Museum. “What is that about?” I wondered, “And what is a Black Holocaust?” There was something written about lynching. Lynching? I was not sure that word had ever been said aloud by any teacher in all my grade school or high school years. Now this Mr. Cameron says that he actually survived being lynched. I had to meet him and see his museum.

A few weeks later, in July 1988, I arrived at the museum. The building’s address was on Wright Street, just a few yards west of N. Dr. Martin Luther King Drive. A sign identified the building as the Sultan Muhammad Islamic Center. I saw no sign for the museum. After knocking on the Wright street door, a young man opened it and slowly looked me up and down as I asked him if the Black Holocaust Museum was there. He simply nodded and pointed me up a set of stairs a few feet away.

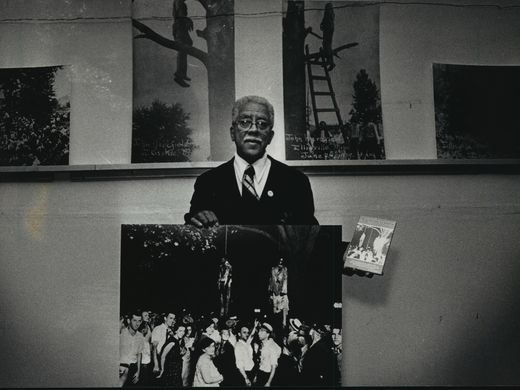

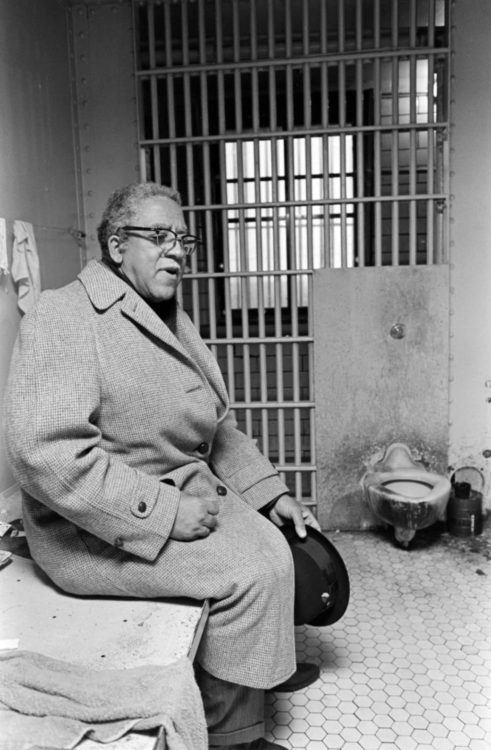

The stairway opened into an expansive, open, second-floor room, with large windows facing east. Across the old hardwood floor, an elderly, gentle-looking man was walking toward me. His was not the broadly smiling approach of a public attraction manager, but rather, Mr. Cameron came forward with the easy, amiable walk of someone greeting a recently-made friend. His smile was warm and welcoming.

I said, “Hi. I came to see your museum.” He introduced himself as we shook hands, and he thanked me for coming. He asked how I had heard about his museum, and I told of the article, explaining that I knew nothing more about it. He nodded and asked if I had a little time to talk. “Sure,” I replied.

I noticed that the large room had no other visitors and there were few exhibits. There were three or four big glass display cases, maybe six or seven feet tall [as I seem to remember them now], plus some poster sized photographs.

Mr. Cameron began telling me his story, pretty much from the beginning, as we slowly walked toward one of the display cases. He was not describing events, like a lecturer might; he was retelling personal memories, as if he was recounting old details and emotions with a friend.

Being a complete stranger to him, I felt a little awkward about that at first, but the more we walked and he talked, the more I became aware that he was not saying anything angry or bitter about his painful past. He was quietly happy to just have someone willing to listen and be supportive. He wanted people to learn and understand.

We never stopped at any particular display case to discuss items within. I asked only simple questions relating to his story. We drifted slowly around. He occasionally pointed to a photo or mentioned some item that related, but telling the story was all important.

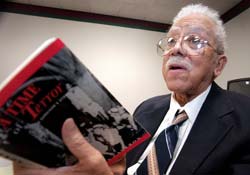

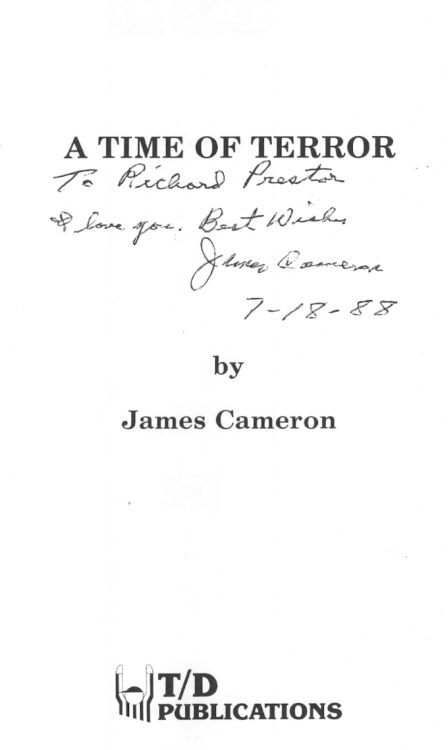

Nearing the end, Mr. Cameron said he had written his story and published a book titled, A Time of Terror. Realizing that I’d already been visiting for over twenty minutes and would need to leave soon, I asked if I could buy his book right there. He smiled a Yes and went to get a copy.

Returning with it, he asked if he could sign it for me. He was a humble gentleman.

On the title page, he wrote, "To Richard Prestor, I love you. James Cameron, 7-18-88."

I treasure my early visit with him, and I’ve kept his special book in a safe place ever since.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.