‘A radical act’: the rich history behind the centuries-long tradition of Black family reunions

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

By Adria R Walker, The Guardian

Festivities usually take place in the summer and often include traditional foods, matching T-shirts and the chance to learn about family ancestry

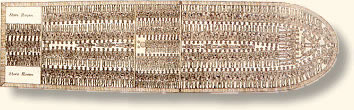

Following emancipation, Jack Johnson had one major goal: to reunite his family. Johnson had been enslaved in North Carolina, Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi, and had 10 children with JoAnna, his first wife, and another 10 with Hettie Brown, his second wife after enslavement.

Though Johnson managed to find nine of the 10 children he had with JoAnna, the family fruitlessly tried to locate the last child, Rufus. Johnson eventually learned that Rufus had been sold with two other enslaved people to a plantation in Texas. But to this day, Johnson’s descendants continue to search for Rufus’s living relatives.

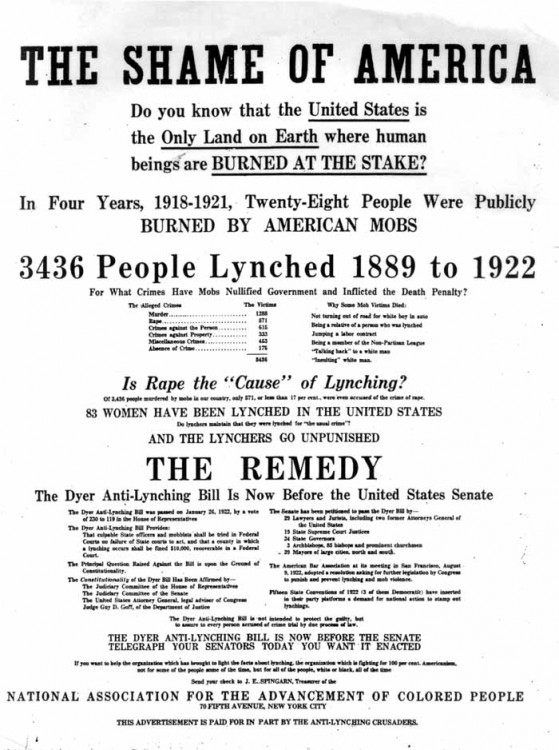

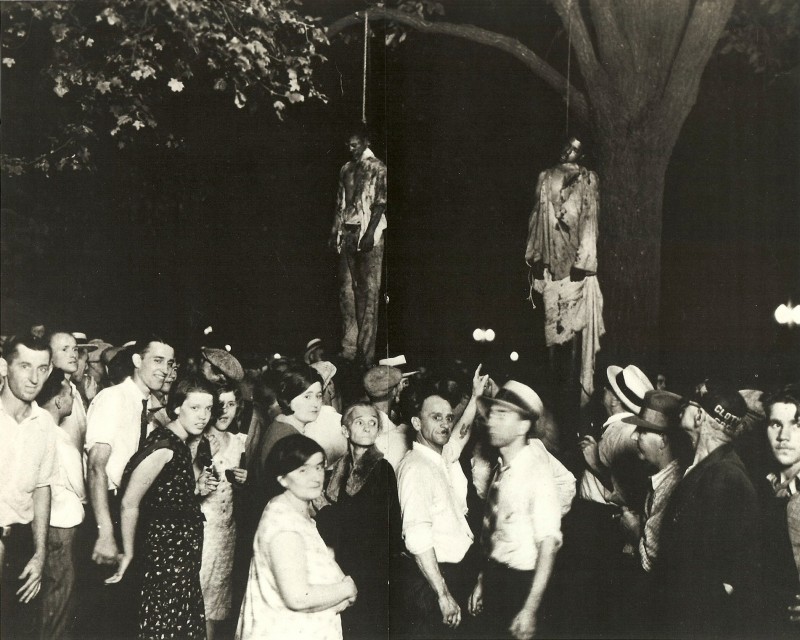

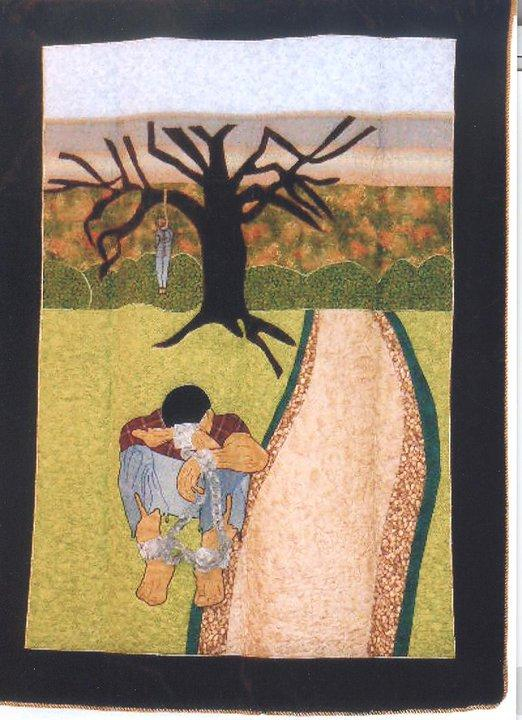

From emancipation to reconstruction, Black families attempted to reconnect after the destruction wrought by slavery. Formerly enslaved people constantly looked for family members who, like Rufus, had been sold away. They placed advertisements in newspapers, asked strangers, searched faces and returned to the lands on which they had been enslaved in hopes of reuniting.

The tradition of Black family reunions was born out of this search, and continues throughout the US today with hundreds of thousands of families connecting, reconnecting and celebrating together annually, usually throughout the summer.

The festivities are a time where family members can meet for the first time, catch up over the time passed since they last saw each other and remember relatives who have passed away. They often include teaching and learning family ancestry and history, and cooking and sharing meals with traditional foods.

Nearly two centuries after Johnson began gathering his family, his descendants met in New Orleans, Louisiana, for a family reunion. Continuing Johnson’s legacy is central to the reunion’s theme. The family has a website, started by Elaine Perryman, dedicated to consolidating and spreading family history.

Ashanté Reese, an associate professor of African and African diaspora studies at the University of Texas at Austin, has been researching Black gatherings for the last two and a half years, attending multiple family reunions across the country.

“This is a thing that makes reunion so special, the tradition that it comes from,” said Reese. “Reading those advertisements, seeing that hope on paper, just made me even more committed to this tradition. These are people who were using the last little bit of money or the last bit of social capital they have. We have all this stuff at our fingertips to be able to stay connected. It feels important to me to honor the longing of people who were recently emancipated by being invested in this tradition.”

The Guardian dives into the research.

After enslavement, it became essential to forge new traditions and, sometimes, families.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.