A Portrait of an Enslaved Man Hung in a Mansion for Over a Century. His Story Is Finally Emerging

Share

Explore Our Galleries

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

by Jo Lawson-Tancred, Artnet News

The painting was jointly acquired by the Mississippi Museum of Art and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

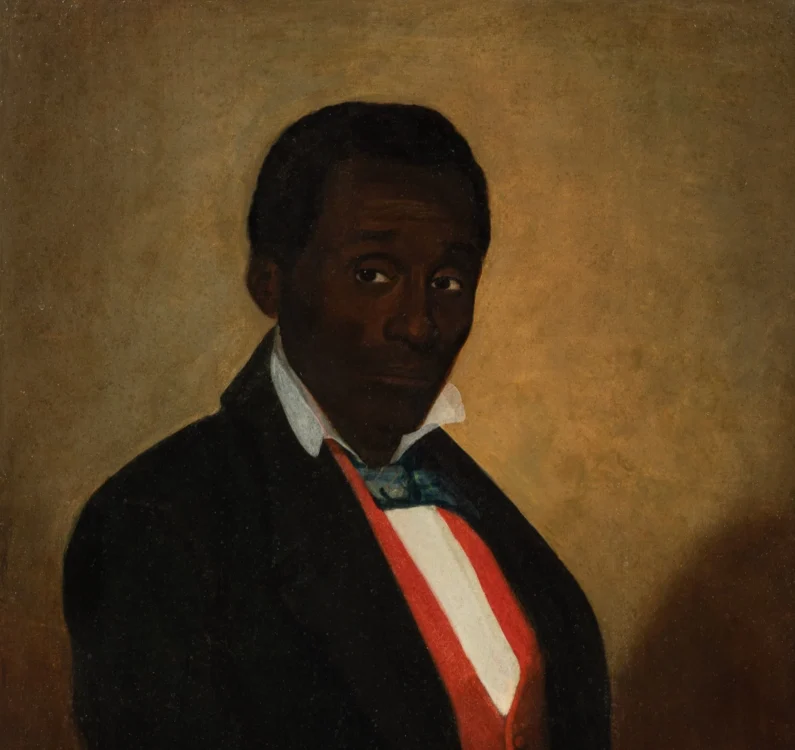

New archival research has revealed the life story of Frederick, the subject of one of only two known formal portraits of people who were enslaved in Mississippi. The hugely significant 19th-century artwork has been jointly acquired by the Mississippi Museum of Art (MMA) and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

The undated Portrait of Frederick, attributed to American painter C. R. Parker, was acquired earlier this year from Neal Auction in New Orleans for $508,750. It will be periodically transferred between MMA in Jackson, Mississippi, and Crystal Bridges in Bentonville, Arkansas. It currently hangs in MMA, where it joins Portrait of Delia by James Reid Lambdin, the only other known portrait of an individual who was enslaved in Mississippi.

The painting previously hung at Longwood, a historic antebellum mansion in the Mississippi town of Natchez. It is the former home of the Nutt family, which enslaved Frederick, but today belongs to the Pilgrimage Garden Club and is open to the public. The club has been criticized by historians for obscuring the site’s violent pre-Civil War history.

[…]

The records show that Frederick was born in around 1802, most likely in Virginia. He was first enslaved by Dr. Rush Nutt, who later established himself as a cotton planter in Mississippi in around 1815. After Rush’s death in 1837, Frederick was among 98 enslaved people to be inherited by his heirs, including Haller Nutt. In an inventory of Rush’s estate, Frederick was given the highest price at $2,000 (or roughly $65,000 in 2025), indicating that his skills were particularly prized. A slightly later inventory, from 1842, noted Frederick’s wife Maria and their four children.

[…]

“The reality for enslaved people on Nutt’s plantations was a horrific life,” said Shannon. “They could, of course, find joy and love in their family as well as outlets like music, oral storytelling, or faith. However, their days were defined by the fact that they were held within a brutal system through the constant threat of violence.”

“Although Frederick occupied a more elite position in the plantation hierarchy, he was subject to this kind of treatment too,” Shannon added.

Discover how Longwood has recently shared some information about its history of slavery.

See classic and mixed-media art in our Special Exhibits.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.