The Published Medical Discoveries of the Enslaved Dr. Caesar

Share

Most Recent Exhibit

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Maria Cunningham

Librarian, Milwaukee Public Library System

Dr. Caesar was an enslaved healer whose cure for rattlesnake poison made an enduring impact on South Carolina medical history. He was the first Black American to have his medical discoveries published.

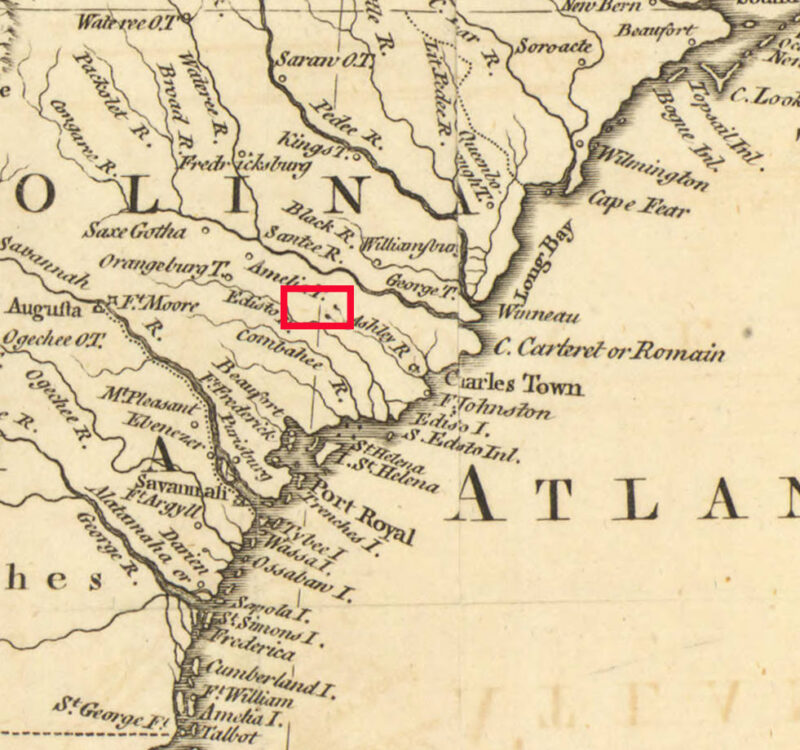

While little is known about the early life of Dr. Caesar, he was believed to have been born around 1683 and lived for approximately 67 years. Caesar, his wife Lily, and two daughters, Lucy and Hannah, were enslaved by John Norman of Beach Hill, SC. Caesar gained recognition in the area for his successful medical cures and extensive knowledge of medicinal plants. Both enslaved Africans, as well as White neighbors, sought out his many cures, including for yaws, pleurisies, fits, distemper, and snake bites.

Poison and Fear

The developing South Carolina rice industry brought enslaved Africans to the area. By 1750, enslaved Africans made up 66% of the population while White colonizers made 33.3% of the population. This large Black population, plus the enslaved Africans’ intimate knowledge of plants and medicinal cures, created an intense fear of poisoning among the colonizers. Newspaper reports of poisoning throughout the colonies stoked these fears and led to horrific executions of the accused enslaved Africans.

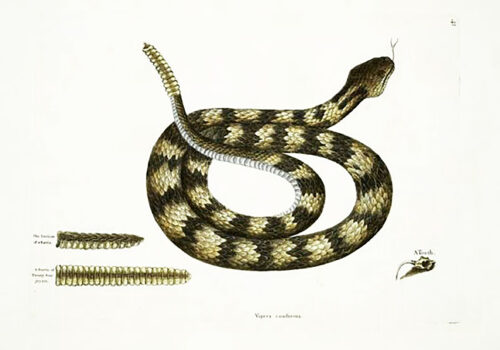

Among the enslaved people, the rate of poisoning was far greater than among Whites for two reasons: 1) conflict between African ethnic groups, and 2) frequent encounters with poisonous snakes during rice cultivation. Cottonmouths, Copperheads, Pigmy, Eastern Diamondback and Timber Rattlesnakes frequently attacked the arms and legs of enslaved Blacks as they labored.

A number of enslaved persons practiced as doctors and healers. They treated their fellow enslaved and were often relied upon by enslavers and other Whites when their customary medicines failed. In the South at this time, there were different health systems the White population and enslaved Africans. While the White population had access to trained doctors and medicines, enslaved Africans received the cheapest possible care that kept them working at the lowest cost to their owners. Only when these treatments failed did owners turn to enslaved healers. In this way, plantation medicine ensured the survival of the folk medicine that the enslaved bought with them from Africa.

Notice, testimony, and decision

In 1749, Caesar and his medical cures caught the attention of the wider public. The first mention of Caesar in any public documents appears November 24, 1749, in the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly:

And another Member acquainted the House that there is a Negro Man named Caesar belonging to Mr. John Norman of Beach Hill who has cured several of the Inhabitants of this Province who had been poisoned by Snakes. And that he had been informed that the said Negro Man Caesar was willing to make a Discovery of the Remedy which he makes use of in such Cases for a reasonable Reward.

To investigate these claims, the Commons established a committee of doctors and local experts to interview Caesar’s patients, test his cures, and determine what his reward would be.

Several witnesses were called before the committee to testify about the effectiveness of Dr. Caesar’s cures. Mr. William Miles testified that his sister and brother were cured of poisoning by Caesar. Henry Middleton, Esq. testified that both he and his Overseer were cured by Caesar. John Norman, Caesar’s enslaver, was also called to testify and informed the Committee that Caesar had cured many people, and he’d never seen him fail in any attempt.

Then, the Committee called Caesar and asked on what conditions he would share his knowledge. Caesar answered that he

expected his freedom, and a moderate competence for life, which he hoped the Committee would be of the opinion deserved one hundred pounds currency per annum. And he proposed to give the Committee any satisfactory experiment of his ability they please as soon as he should be able to provide himself with the necessary Ingredients.

Surprisingly, the Committee agreed to this. Before they could proceed though, they had to determine a fair price to compensate owner John Norman. After a lengthy process involving lawyers and arbitrators, a provision of £500 (pounds) was paid to Norman for the appraised value of the man he enslaved.

Dr Caesar’s Cure

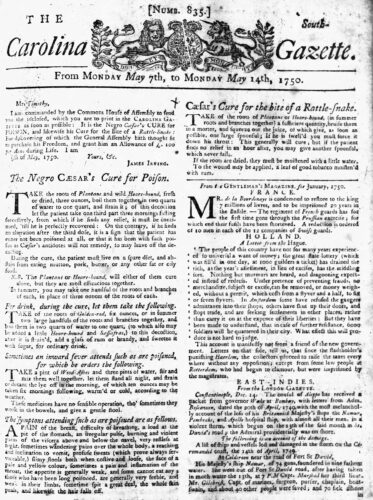

After Caesar’s cures were shared, the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly ordered that a copy of them be given to a local printer for public circulation. On May 14th, 1750, the front page of the South Carolina Gazette printed the full text of “The Negro CÆSAR’s Cure for Poison.”

Take the roots of Plantane and wild Hoare-hound, fresh or dried, three ounces; boil them together in two quarts of water to one quart, and strain it; of this decoction let the patient take one third part three mornings, fasting successively, from which is he finds any relief, it must be continued till he is perfectly recovered. On the contrary, if he finds no alteration after the third dose, it is a sign that the patient has either not been poisoned at all, or that it has been with such poison as Caesar’s antidotes will not remedy, so may leave off the decoction. During the cure the patient must live on a spare diet, and abstain from eating mutton, pork, butter, or any other fat or oily food.

N.B. The Plantane or Hoar Hound will, either of them, cure alone, but they are most efficacious together.

In summer you may take one handful of the roots and branches of each, in place of three ounces of the roots of each.

For drink during the cure, let them take the following.

Take of the roots of Golden Rod, six ounces, or in summer two large handfuls of the roots and branches together, and boil them in two quarts of water to one quart (to which also may be added a little Hoare Hound and sassafras); to this decoction, after it is strained, add a glass of rum or brandy, and sweeten it with sugar for ordinary drink.

Sometimes an inward fever attends such as are poisoned for which he orders the following,

Take a pint of wood ashes and three pints of water; stir and mix them well together; let them stand all night, and strain or decant the lye of[f] in the morning, of which ten ounces may be taken six mornings following, warmed or cold, according to the weather. These medicines have no sensible operation, though sometimes they work in the bowels, and give a gentle stool.

The symptoms attending such as are poisoned are as follows,

A pain in the breast, difficulty in breathing, a load at the pit of the stomach, an irregular pulse, burning and violent pains of the viscera above and below the navel, very restless at night, sometimes wandering pains over the whole body, a reaching [i.e., retching] and inclination to vomit, profuse sweats (which prove always serviceable), slimy stools both when costive and loose, the face of a pale and yellow colour, sometimes a pain and inflamation of the throat; the appetite is generally weak, and some cannot eat any; those who have been long poisoned are generally very feeble and weak in their limbs, sometimes spit a great deal; the whole skin peals, and likewise the hair falls out.

Caesar’s Cure for the Bite of A Rattle-Snake.

Take the roots of Plantane or Hoare Hound (in summer roots and branches together) a sufficient quantity; bruise them in a mortar, and squeeze out the juice, of which give, as soon as possible, one large spoonful; if he is swelled you must force it down his throat. This generally will cure, but, if the patient finds no relief in an hour after, you may give another spoonful, which never fails.

If the roots are dried, they must be moistened with a little water.

To the wound may be applied a leaf of good tobacco moistened with rum.

Freedom and Death

Dr. Caesar was released from bondage in 1750 with an annual annuity of £100 a year for the rest of his life. Although Dr Caesar was freed, he had but few years to enjoy his freedom. He is believed to have died sometime before March 1754.

The Commons House continued to pay Caesar’s annual annuity until April 1754, when the House journal recorded a payment of £70.16.08 to the “Estate of Dr. Caesar, deceased, 8 months and a half annuity.”

At the time of Caesar’s death, his wife Lily and daughter Hannah were still enslaved by John Norman.

Reach and influence

Demand for Caesar’s cures was so great that the Carolina Gazette reprinted them the following year in its February 25–March 4, 1751, issue.

From there it found its way into publications across North America and even England. Caesar’s cure was printed in a 1750 issue of Gentleman’s Magazine of London, John Tobler’s 1777 South Carolina and Georgia Almanack, the Massachusetts Magazine in 1792, and the book Domestic Medicine by William Buchan in 1797.

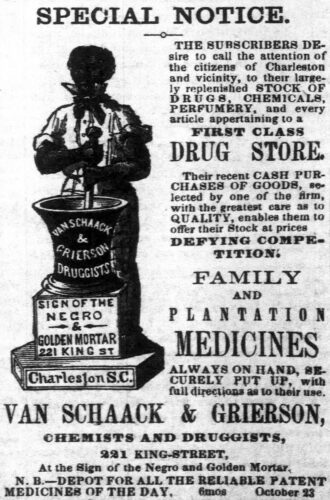

Remedies introduced or popularized by enslaved

Africans quickly became absorbed into White medical practice. Many pharmacies and apothecaries used images of African and Native Americans to market their own wares and give the appearance of credibility. Newspaper ads for the druggist Van Schaak & Grierson in Charleston, South Carolina began to feature the image of an African holding a pestle between 1761-62. The ad instructs patrons to find their establishment under “the sign of the Negro and the Golden Mortar.” It was thought that the image depicted Cesar, given his notoriety in the area.

Although the colonizers benefitted from Caesar’s cures, they quickly introduced a law forbidding any other African American healer from practicing medicine.

“Henceforth, no negroes or other slaves (commonly called doctors,) shall hereafter be suffered or permitted to administer any medicine, or pretended medicine, to any other slave, but at the instance or by the direction of some white person.”

Maria Cunningham is Librarian for the Milwaukee Public Library in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She has volunteered for ABHM for several years and curated the travelling exhibit on Dr. Cameron’s writings.

Bibliography & further reading

Buchan, William, M.D. Domestic Medicine. 1798. Printed by and for James Lyon, at Voltaire's Head, Fairhaven, VT.

Butler, Nic, Ph.D. "Doctor Caesar and His Antidote for Poison in 1750." February 12, 2021. Accessed [June 6, 2024]. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/doctor-caesar-and-his-antidote-poison-1750.

De Brahm, John Gerar William, William Bull, and Thomas Jefferys. A Map of South Carolina and a Part of Georgia. Containing the Whole Sea-Coast; All the Islands, Inlets, Rivers, Creeks, Parishes, Townships, Boroughs, Roads, and Bridges; as Also, Several Plantations, with Their Proper Boundary-Lines, Their Names, and the Names of Their Proprietors. London: T. Jefferys, 1757. Map. Accessed [June 6, 2024]. URL: https://www.loc.gov/item/75693002/.

Easterby, J. H., and Ruth S. Green, eds. The Colonial Records of South Carolina: The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, March 28, 1749–March 19, 1750. Columbia: South Carolina Archives Department, 1962, pp. 293–94.

Gherini, Claire. "Valuing 'Caesar's and Sampson's Cures'." August 18, 2015. Accessed [June 6, 2024]. https://recipes.hypotheses.org/6419#_ftn2.

Morgan, Philip D. Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry. Chapel Hill: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by the University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. "Vipera caudisona, The Rattle-Snake; The Section of a Rattle; A Rattle of Twenty-four joynts; A Tooth." New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed [June 6, 2024]. URL: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-66e7-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Rogers, George C., and C. James Taylor. A South Carolina Chronology, 1497-1992. 2nd ed. Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press, 1994.

"The Negro's Cure for Poison." The South Carolina Gazette, May 14, 1750. Accessed [June 6, 2024]

Woodville, William. Medical Botany: Containing Systematic and General Descriptions, with Plates of All the Medicinal Plants, Indigenous and Exotic, Comprehended in the Catalogues of the Materia Medica, as Published by the Royal Colleges of Physicians of London and Edinburgh. 2nd ed. London: Phillips, 1810

Van Schaak & Grierson Advertisement." Charleston Daily Courier, May 4, 1859.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.