Photographs from WHS Freedom Summer Archive

Share

Picturing Black History

Explore Our Galleries

Most Recent Exhibit

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Scholar-Griot: Adamali De La Cruz

Editor: Robert S. Smith, PhD

Introduction

After Freedom Summer came to a close, activists and residents of Mississippi retained materials and photos documenting to the project. The documents and photos may have been forever lost had it not been for the foresight of graduate students working at the Wisconsin Historical Society (WHS) in the late 1960s. Many of the students working at WHS had prior experience with the Civil Rights movement in the South and believed it was necessary to collect documents and photos related to the movement for archival purposes. Their willingness to drive South and collect the stories of the local people has led to WHS having one of the most exhaustive collections in the country documenting the grassroots efforts and local events of the Civil Rights Movement.

These archives have since been used to curate a traveling exhibit developed by the Wisconsin Historical Society, Risking Everything and an accompanying collection of primary sources in Michael Edmonds’ Risking Everything: A Freedom Summer Reader. ABHM has also used these archives to create an in-depth virtual exhibit connecting the struggle for civil rights in Mississippi with the movement in Milwaukee, WI.

Frame 58: Woman Casting Freedom Vote, circa 1964

This photo highlights the interracial coalition of the 1964 Freedom Election. We see two women casting Freedom Votes or possibly working the election and the background is a run down cabin. In 1964, a coalition of civil rights groups, including the Student Non Violent Coordinating Committee, formed the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) and coordinated a plan that would attempt to register African Americans to vote, start a new political party called the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, educate children and adults through Freedom Schools, and later a run a parallel Freedom Election. This image specifically highlights the desire African Americans had to participate in elections. However, 1964’s Freedom Summer would not have been possible without the interracial and intersectional approach taken by the movement strategists. Northern volunteers (mostly white college students) were trained by locals about racism faced in Mississippi. Black Mississippians were willing to risk their lives to house volunteers and organize themselves in order to fight segregation and disenfranchisement in the state.

Frame 19: "We Want to Vote,” circa 1964

This photo is from Freedom Day in Greenwood, MS, likely in 1964. The viewer can clearly see the protest signs, the police bus in the background, and the policeman holding a bullhorn. The expressions and postures of the protestors show determination. The Freedom Day programs were suggested by Freedom Summer staff as a way to involve the whole community to create a real sense of achievement and gather evidence for a federal lawsuit challenging voter suppression. Involving the community and establishing momentum was key for breaking down the fear and apathy instilled in the Black community due to centuries of oppression and discrimination by southern whites. Despite the peaceful nature of Freedom Summer activities, on this Freedom Day in Greenwood, over 100 residents, Freedom Summer staff, and volunteers were taken to jail on the police bus.

Voting Rights Protesters, circa 1964

Like Greenwood, other cities in Mississippi were mobilizing to challenge voter suppression. This particular image is an example of the interracial organizing that was done in Hattiesburg. Again, we can see the interracial coalition that was created in Mississippi. The signs seen here clearly articulate the goals of the movement - to secure voting rights for all in a country that promises such.

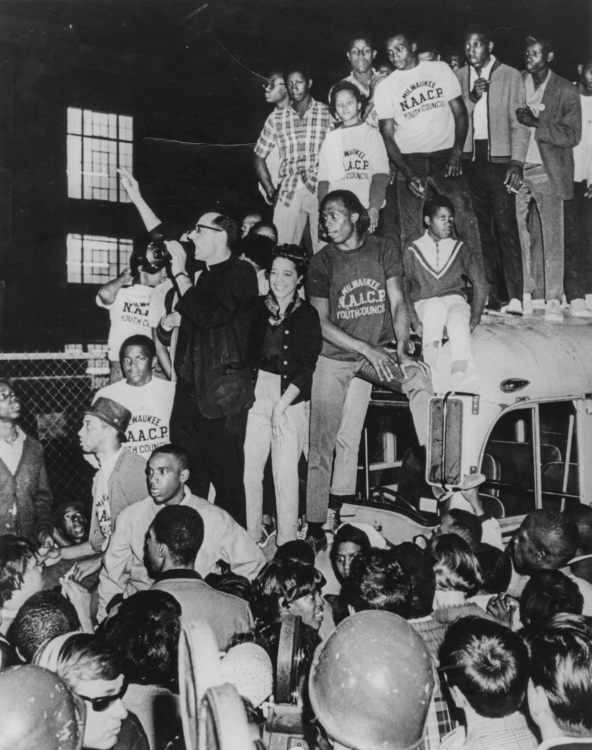

Frame 38: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party District Meeting, circa 1964

One of the most significant achievements of Freedom Summer came in the form of establishing a political party. This image shows the level of planning and organizing that Freedom Summer staff and volunteers did to make the party a reality. The viewer can see the signs listing different counties, the interracial collaboration, and the engagement by the audience. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) was established to challenge what was effectively a one party system in Mississippi. Civil rights activist Victoria Gray, Fannie Lou Hamer, and others were platformed as candidates for seats to Congress and, in the Freedom Election of November 1964, every single MFDP candidate received more votes than the Democratic Party candidates who were also on the Freedom ballots.

Frame 43: Mrs. Hamer and Microphones on Television, circa 1964

A lifelong Mississippian, Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer was well versed in the realities of working class African Americans in the state. As a civil rights activist, she also knew the risks everyday people were taking by supporting the movement. She was drawn to the movement’s efforts for voter registration and later became a candidate for Congress through the MFDP. This put her in the national spotlight and she used it as a way to speak about her experiences in Mississippi. A powerful orator, this image shows the passion and determination that Mrs. Hamer brought to every appearance.

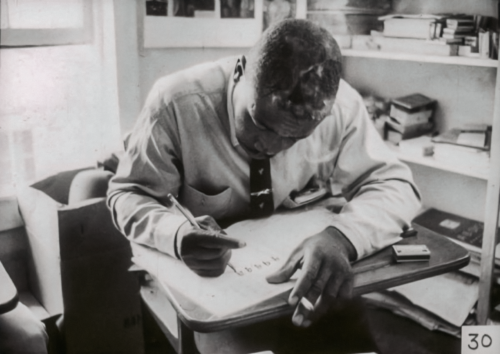

Freedom School, 1964

The Freedom Schools were created to fulfill a need that was not being met by the state: basic education. Initially considered a peripheral project by some, the schools were incredibly successful with nearly 3,000 students taking classes from 175 teachers in 40 schools across the state of Mississippi. The Freedom Schools were also intended to challenge notions of African American inferiority that many students, both Black and white, had been taught in schools. With curriculums created by Freedom Summer staff, many white volunteers facilitated the classes to children and adults all over the state. This photo shows a group of about 10 students listening to their teacher as they sit outside. The children look engaged, showing a hunger for this kind of education that had previously been denied to them.

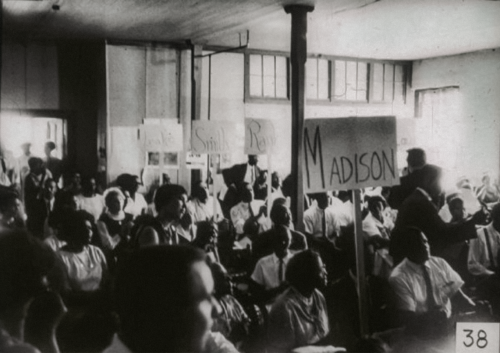

Frame 30: Man Learning to Read and Write, circa 1964

Many African Americans in the 1960s had little or no access to formal education in Mississippi. In response to this, COFO and Freedom Summer staff created Freedom Schools. These Freedom Schools attracted both young children, teenagers, and adults to learn to read and write. Most people in this country today are taught to read and write by the time we turn 5 or 6 in school, yet the person in this photograph is an adult man, which elicits an emotional response in the viewer. The cigarette further adds to this juxtaposition of something very adult with the desk and task that feels like a cornerstone of childhood. While his expression is not fully clear, the lines in his forehead indicate dedication to his studies.

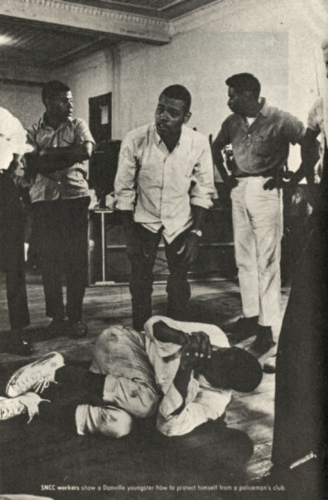

SNCC Workers Teach Self-Defense, 1960s

It’s difficult for a modern viewer to truly understand the level of danger that existed in Mississippi for civil rights activists, especially those who were local and Black. In an attempt to keep the northern white volunteers safe--who were unfamiliar with and in a sense, naive, about the racial violence in the South--SNCC facilitated self defense training and simulations. The purpose of the training was to ensure that if a situation became tense and dangerous, the volunteers would maintain their nonviolent postures and responses, protecting the image of the movement and themselves. In this photo, SNCC workers teach a young man how to protect his vital organs in the case of an encounter with a policeman’s club.The need for self defense and awareness became extremely clear on the first day of Freedom Summer with the disappearance (and later confirmed deaths) of three activists: Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner. Other documents by SNCC reveal that volunteers were also taught how to canvas; how to engage with the press, strangers, and law enforcement; and what to do in case of arrest.

Frame 21: Police Grabbing Girl by Arm - She is Not Intimidated, 1964

While many acts of violence towards civil rights activists happened without being captured by a camera lens, there were also many that were documented and then seen by people across the world. One iconic image that many are familiar with is the photograph of a young John Lewis being dragged and beaten by law enforcement on “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, AL on March 7th, 1965. This photo, taken almost a year prior, 15 year old Annie Lee Turner is being similarly dragged by a policeman. Despite the situation, she holds her head up and a shadow on her arm indicates her attempt to pull away. The policeman is showing no restraint. The photo also shows other policemen who are making no effort to stop or mitigate the unnecessary force. A reporter in the background runs to get a shot. Perhaps, like the photographer who captured this image, they too felt the need to document a moment where even young people were subject to violence.

Click here to see the collection online at the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Click here to view ABHM's gallery Risking Everything.

Exhibit Credits

Scholar-Griot, Adamali De La Cruz is the Education and Griot Coordinator at America’s Black Holocaust Museum. She is a graduate of Marquette University's History department with a focus on medieval studies. She joined ABHM as a Griot/Center for Urban Research and Teaching Outreach (CURTO) Intern in 2022 and formally joined the ABHM Ed. Dept in 2023. As the Education and Griot Coordinator, Adamali has developed the Junior Griot Program for high school students, coordinates with volunteers, has assisted in formalizing the college internship program at ABHM, and writing of virtual exhibits and other public history projects that ABHM contributes to.

Editor, Dr. Robert S. Smith is the Harry G. John Professor of History and the Director of the Center for Urban Research, Teaching & Outreach at Marquette University. He serves as ABHM’s Director of Education and Resident Historian. His research and teaching interests include African American history, civil rights history, and exploring the intersections of race and law. Dr. Smith is the author of Black Liberation from Reconstruction to Black Lives Matter and Race, Labor & Civil Rights; Griggs v. Duke Power and the Struggle for Equal Employment Opportunity. Prior to joining Marquette University, Dr. Smith served as the Associate Vice Chancellor for Global Inclusion & Engagement and Director of the Cultures & Communities Program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. And, Rob is the proud father of Henderson Marcellus Smith.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.