Photographs from UWM March on Milwaukee Archive

Share

Picturing Black History

Explore Our Galleries

Most Recent Exhibit

Breaking News!

Today's news and culture by Black and other reporters in the Black and mainstream media.

Ways to Support ABHM?

Student-Griot: Mya Mays

Editor: Robert S. Smith, PhD

Introduction to Collection

Civil Rights activists did not just work in the South. Across the country, organizers worked for job equality, better education, and fair housing. Cities were also segregated, as redlining and restrictive covenants confined Black communities to certain neighborhoods.

Milwaukee’s fair housing movement played an important role in influencing national legislation. Vel Phillips, the first African American on Milwaukee’s Common Council, initially introduced a citywide fair housing ordinance in 1962. To support Phillips’ ordinance, the NAACP Youth Council, outspoken advocate Father James Groppi, and many others marched, picketed, and boycotted businesses. Thanks in part to their sustained efforts (including marching for 200 consecutive days), President Johnson signed federal fair housing legislation in April 1968.

About the collection: This digital collection presents primary sources from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries and the Wisconsin Historical Society, providing a window into Milwaukee’s civil rights history. During the 1960s, community members waged protests, boycotts, and legislative battles against segregation and discriminatory practices in schools, housing, and social clubs. The efforts of these activists and their opponents are vividly documented in the primary sources found here, including photographs, unedited news film footage, text documents, and oral history interviews. This website also includes educational materials, including a bibliography and timeline, to enhance understanding of the primary sources. The March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project seeks to make Milwaukee’s place in the national struggle for racial equality more accessible, engaging, and interactive.

The Freedom House on fire, 1967

As a direct response to the activism of the NAACP Youth Council, a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan bombed the headquarters of Milwaukee’s NAACP. After the bombing, the Youth Council went to the police and asked for protection. In response, the police said, “If you don’t want any trouble, don’t make trouble for yourself.” This is not the Deep South; this is in a city north of the Mason-Dixon line. The following images are often only associated with this kind of racial violence in southern locales.

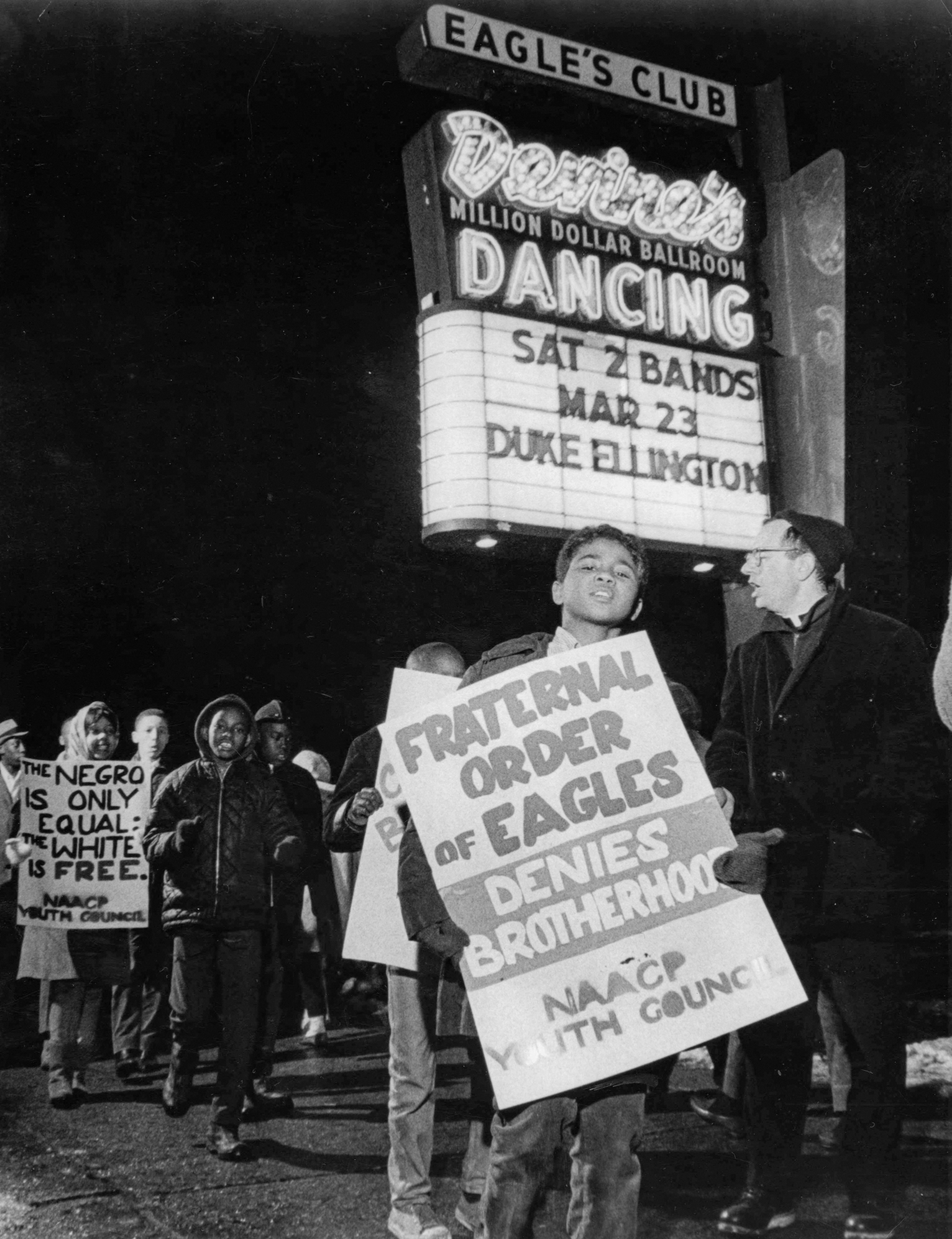

NAACP Youth Council demonstration of Milwaukee Eagles Club, 1966

This photograph captures the NAACP Youth Council protesting an incredible contradiction. To the right of them in the photo is their advisor and advisee, Father Groppi. African Americans were not allowed to join Milwaukee’s Eagles Club because of its all-white membership policy, membership which included local elected politicians and judges. The Eagles Club was not just a place for entertainment; it was also a place where decisions were made and power was built. If you also look at the marquee of the Eagles Club, you can see that Duke Ellington would be performing; under the racist policies of the Club, he and his band could not have bought tickets to their own show nor attended as audience members.

Confrontation between Milwaukee police and the Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council, circa 1967-1968

This image embraces the tension of the moment and juxtaposes the peaceful postures of the council with the militarism and momentum of the police. On the left of the picture, you have the stance of the NAACP Youth Council, which includes young men maintaining control of their own physical expressions, hands, and movements, but at the same time are certainly fearful of what might happen. Then, on the right of the picture, you have the Milwaukee Police advancing on the peaceful protesters with clubs and body armor. What other differences can you spot between the two sides of this photo?

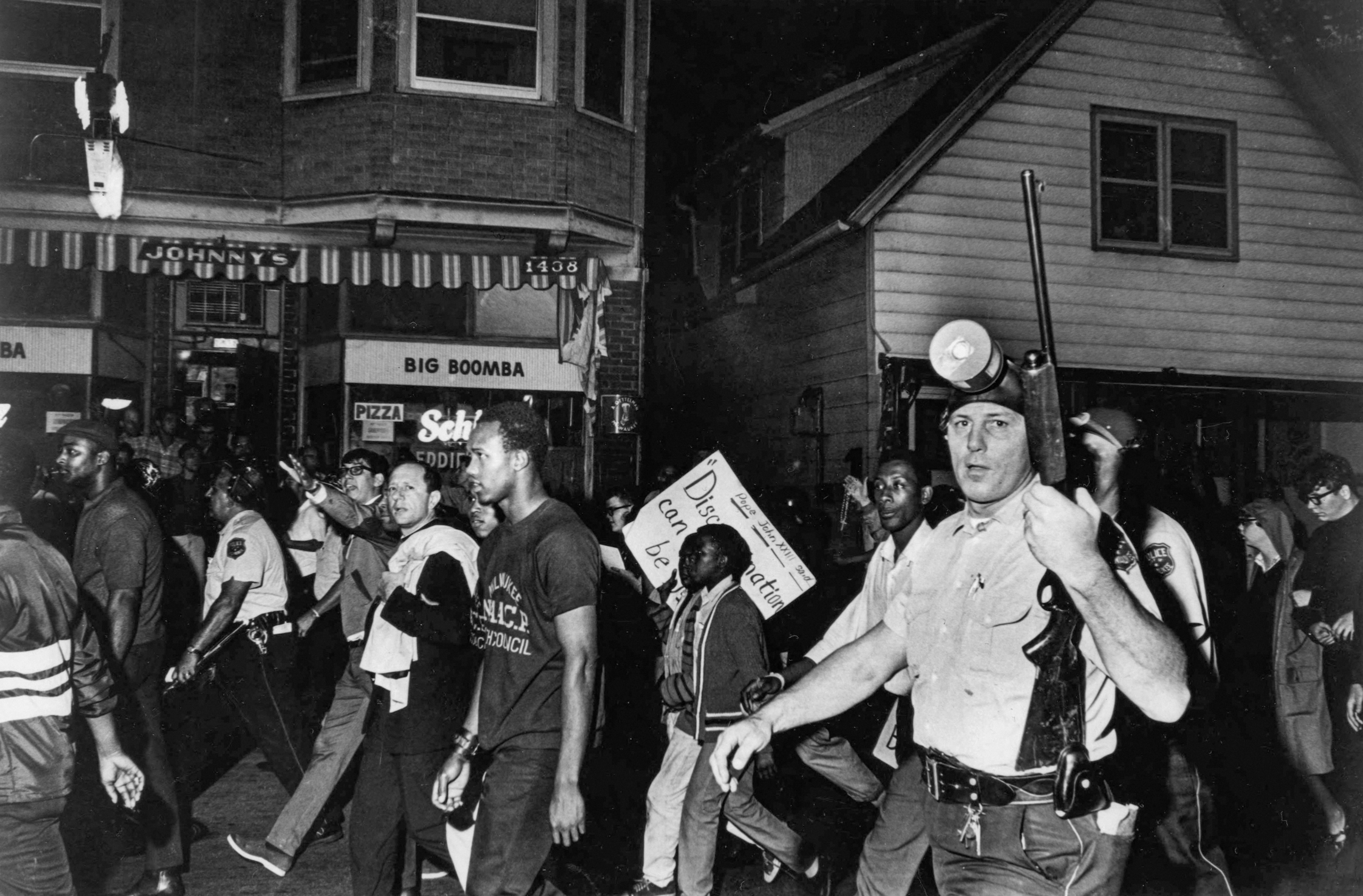

NAACP march with police escort, circa 1967-1968

This march with the NAACP and Father Groppi may be on North Broadway. This was part of the 200 days of continuous protest organized by the NAACP to demand fair and open housing. This local movement had a conflicted relationship with the police, as evidenced by many of the photographs in this collection. The city government was often suspicious or hostile to the Youth Council’s activities, and the police were used to surveil the Youth Council. Yet the police were also tasked with protecting protesters during marches, walking alongside marchers they may have recently been harassing.

Vel Phillips at Common Council Meeting, before 1971

In this photograph, you can see the intense emotions on Common Council members' faces, ranging from indifference to anger to the worry on Vel Phillips’ own face. Between 1962 and 1968, Vel Phillips repeatedly brought fair housing bills before the Common Council. Each time she brought it forward for a vote, she was defeated unanimously, except for her own vote. Vel Phillips introduced her fair housing ordinance to the Milwaukee Common Council four times between 1962 and 1967, and it was defeated by a vote of 13 to 1 each time.

Vel Phillips and Milwaukee NAACP, circa 1960's

Vel Phillips smiles as she is lifted up on the shoulders of NAACP Youth Council; Father James Groppi speaks to the crowd in St. Boniface Catholic Church in 1967. Both were later arrested. “They dumped urine on us and rotten eggs,” she once said about a march that ended with her arrest. Comparing this photo to the one above, what do you notice about the shift in emotion with Vel in Council Chambers versus when she is out protesting with the activists? You can imagine and see the toll working with local government took on her versus the joy and hope she felt being a part of the movement on the streets with all these young people.

NAACP march to honor Martin Luther King Jr., 1968

The Commandos, Youth Council, Father Groppi, Vel Phillips, and many others supporters for fair housing marched 200 consecutive days. The open housing marches ended in March 1968 as they pondered what next steps to take to achieve open housing for all. Not even two weeks later, Dr. King was assassinated on April 4th, 1968 in Memphis, where he was helping striking garbage workers to unionize. Dr. King had been a huge admirer of activism in Milwaukee, and Milwaukee engineered one of the largest non-violent responses to his death, pictured here. Milwaukee activists had become really good at nonviolent protest expanding on the methods learned from fellow activists in the South. Two days after this protest, Congress passed and President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which included Title VIII, The Fair Housing Act, covering 80% of housing across the land.

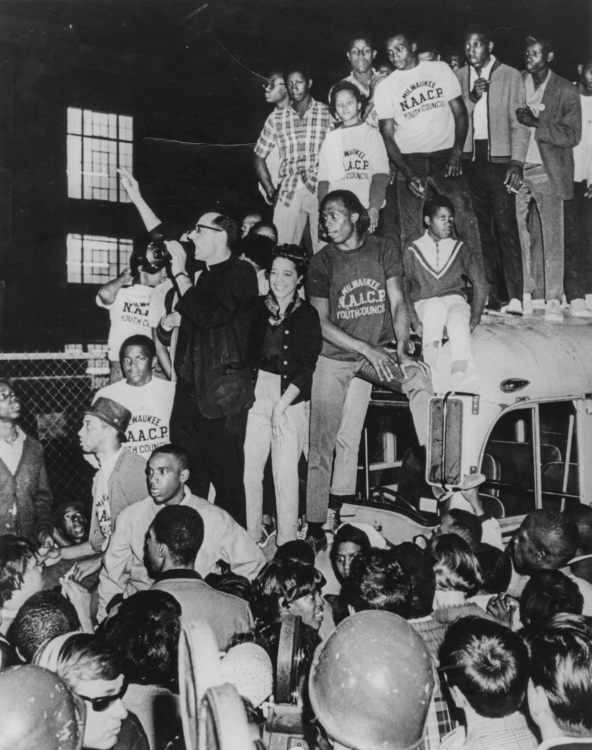

James Groppi and Vel Phillips on school bus, circa 1967-1968

Vel Phillips on the hood of a bus next to Father Groppi surrounded by Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council members. This is a photo of one of the 200 marches that took place in 1968. The photo perfectly captures the youthful energy and leadership of the movement, with Vel all smiles and Groppi on the megaphone.

Click here to view the March On Milwaukee - Civil Rights History Project at UWM online.

Exhibit Credits

Student-Griot, Mya Mays is a University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee student participating in the Panther Edge Internship Program and currently serves as an intern in the Education Department at America’s Black Holocaust Museum. In her role as a museum intern, she supports research and educational initiatives that help connect history and community engagement.

Editor, Dr. Robert S. Smith is the Harry G. John Professor of History and the Director of the Center for Urban Research, Teaching & Outreach at Marquette University. He serves as ABHM’s Director of Education and Resident Historian. His research and teaching interests include African American history, civil rights history, and exploring the intersections of race and law. Dr. Smith is the author of Black Liberation from Reconstruction to Black Lives Matter and Race, Labor & Civil Rights; Griggs v. Duke Power and the Struggle for Equal Employment Opportunity. Prior to joining Marquette University, Dr. Smith served as the Associate Vice Chancellor for Global Inclusion & Engagement and Director of the Cultures & Communities Program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. And, Rob is the proud father of Henderson Marcellus Smith.

Comments Are Welcome

Note: We moderate submissions in order to create a space for meaningful dialogue, a space where museum visitors – adults and youth –– can exchange informed, thoughtful, and relevant comments that add value to our exhibits.

Racial slurs, personal attacks, obscenity, profanity, and SHOUTING do not meet the above standard. Such comments are posted in the exhibit Hateful Speech. Commercial promotions, impersonations, and incoherent comments likewise fail to meet our goals, so will not be posted. Submissions longer than 120 words will be shortened.

See our full Comments Policy here.